Methodology

Introduction

This document details the scope and methodology of CountryRisk.io’s framework in determining its Sovereign Risk Scores. These scores denote the indicative level of sovereign credit risk of each country based on seven risk determinant sections. These are: (1) economic growth prospects, (2) institutions and governance, (3) monetary stability, (4) fiscal solvency and public debt, (5) sovereign liquidity, (6) external debt sustainability and (7) private sector strength.

Overview

The objective of the CountryRisk.io Sovereign Risk Scores is to classify countries according to their willingness and ability to honour foreign currency government bond obligations. The scores are largely derived from CountryRisk.io’s sovereign rating model; however, they do not take into account the qualitative indicators that appear in that model. This is explained in more detail in the Sovereign Rating Methodology . Simply put, the Sovereign Risk Scores only consider quantitative indicators. Table 1 below lists the individual indicators for each of the seven sections.

| Risk Section | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Economic growth prospects | GDP per capita Real GDP growth (5 year average) Real GDP volatility (5 year window) Gross national savings (% GDP) Trade openness Research and development expenditures (% GDP) Researchers in R&D (per million people) Unemployment rate Youth unemployment rate Labour force participation rate |

| Institutions and governance | Rule of law Control of corruption Government effectiveness Regulatory quality Voice and accountability Political stability Level of statistical quality |

| Monetary stability | Inflation rate (5 year average) Inflation volatility (5 year window) Change of domestic credit to GDP ratio (5 year window) Real interest rate |

| Fiscal solvency and public debt | General government debt to GDP Public external debt to GDP Public external debt to total external debt Revenue efficiency |

| Sovereign liquidity | Fiscal balance (% of GDP) Current account balance (% of GDP) Export growth (5 year average) Interest payments to tax revenues Debt service (% of exports) |

| External debt sustainability | Net external debt (% of GDP) Net external debt (% of exports) Short-term external debt to FX reserves Import coverage (in months) External financing requirements IMF reserves adequacy ratio Short-term external debt to total external debt Foreign currency denominated external debt to total external debt |

| Private sector strength | Non-performing loans to total loans Regulatory capital to risk-weighted assets Return on equity Liquid assets to short-term liabilities Household debt to GDP |

Like CountryRisk.io’s sovereign rating model, the Scores focus strictly on sovereign governments at a national level, excluding regional governments and quasi-sovereign entities.

Risk Sections

Economic growth prospects

The structure of a country’s economy influences its growth prospects and resilience. In turn, this determines its ability to generate sustainable revenues and service the government’s obligations. A country’s economic structure is, therefore, a key determinant of its risk level.

To assess a country’s economic prospects, we analyse its historical and current growth trends. We also look at its fundamental drivers of long-term growth, such as human capital (e.g. research and development expenditure), integration with the global economy and labour market aspects (e.g. unemployment rate, labour force participation rate). An economy with a high gross domestic product (GDP) per capita or favourable growth outlook is more likely to provide the government with stable tax revenues. Conversely, a country with limited prospects for increasing the per capita income of its citizens will likely experience persistent revenue shortfalls and, therefore, need to borrow regularly—either in its domestic capital markets or abroad—to bridge the inevitable deficits.

Institutions and governance

Robust political institutions serve to anchor a country during times of economic instability and mitigate concerns that a government might not service its debt. Countries with a robust legal system, established mechanisms for fighting corruption, an effective government, a healthy regulatory regime and political stability and transparency receive lower risk scores in our framework. In addition, this risk section includes an indicator that assesses the overall ease of doing business within that country.

Monetary stability

Sound monetary policy is a foundation for stable growth and reduces the risk of economic fluctuations during periods of stress. This indicator assesses monetary authorities’ success in using the tools at their disposal flexibly and independently, without interference from governments whose goals may not align with those of the central bank.

A growing number of central banks in both advanced and emerging economies identify price stability as their primary monetary objective. So, a stable inflationary environment indicates the extent to which central banks have the ability to achieve that goal. This is important as it minimises risks in related channels, such as the banking and financial sector as well as its currency exchange rate.

Fiscal solvency and public debt

The sustainability of a sovereign’s fiscal deficits and debt is crucial to determining sovereign credit risk. In assessing the former, CountryRisk.io looks at the size of the government’s revenues and debt.

Sovereign liquidity

Whereas our assessment of “fiscal solvency and public debt” focuses on the starting condition (i.e. level of debt in comparison to productive capacity), “sovereign liquidity” assesses the momentum of key indicators such as fiscal & current account balance and debt service capacity.

External debt sustainability

CountryRisk.io’s analysis of a country’s external position considers its external liquidity and external debt viability. We use several metrics to measure external liquidity, including import coverage, external financing requirements as a percentage of GDP, and the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) reserve adequacy ratio (RAR). Import coverage—expressed in numbers of months—depicts the adequacy of foreign exchange reserves to pay for imports. While this is a useful measure of external liquidity, it is narrowly defined and more appropriate for low-income countries, as defined by the IMF. We regard external financing requirements and RARs as more robust indicators of external liquidity, with the former taking into account sources of external vulnerability such as the size of a country’s current account balance, short-term external debt and principal payments. Clearly, without sufficient useable foreign exchange reserves, a country that is running current account deficits and facing significant payments due in the next twelve months is likely to run into liquidity issues.

Private sector strength

Strong and stable private and banking sectors are vital for the efficient capital allocation countries need to finance sustainable economic growth. History shows us that banking sector crises tend to result in significant economic output losses, lower growth prospects and, due to contingent liabilities, considerable deterioration in sovereign credit quality. This risk section includes, among other indicators, non-performing loan ratio (as a proxy for credit quality in the banking sector and overall economy), capitalisation ratio and overall indebtedness of households.

Data

In calculating the Sovereign Risk Index, CountryRisk.io utilises a wide range of indicators selected for their informational value and data availability. We source the data for these indicators from a wide range of reputable international multilateral institutions, including the World Bank and IMF.

Country coverage

The underlying geographic universe covers 190 countries and territories. However, country coverage varies across indicators. Besides country coverage, we selected the indicators on the basis of other criteria, such as:

- Available history: Is there a long history of regular updates? This allows us to assess whether an indicator is too volatile.

- Reporting lag/latest datapoint: When was the index last updated? Will it be updated again in the future?

- Methodology changes: Is the methodology used to calculate the index revised regularly? Frequent and significant changes lead to a lack of comparability over time, while modest changes suggest that the indicator continues to be developed to reflect a changing environment.

- Basis of indicator: Is the indicator based on original (survey) data, or is it a composite of other indicators?

| Share of Available Indicators | < 20% | 20% < 40% | 40% < 60% | 60% < 80% | 80% < 100% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Quality Classification | Very Poor | Poor | Medium | Good | Very Good |

As part of the index calculation, CountryRisk.io also provides a quantitative measure of data quality for each country. We base this measure on the number of available indicators for each country divided by the total number of indicators included in the model. The mapping table between the share of available indicators and data quality is shown above.

Methodology

CountryRisk.io uses a purely quantitative approach to calculate its Sovereign Risk Scores.

Statistical models use quantitative methods to establish relationships between certain factors—for example, the rule of law—and the strength of debt sustainability in each country. Such models are less prone to bias than purely qualitative methods, which makes them useful in terms of tractability of results and consistency over time. That said, we also understand that statistical models are vulnerable to biases that can influence the process of selecting, specifying and calibrating the model. Furthermore, some indicators (e.g. institutional quality) reflect the subjective assessments of survey participants, although the large number of respondents significantly mitigates the adverse impact of that subjectivity.

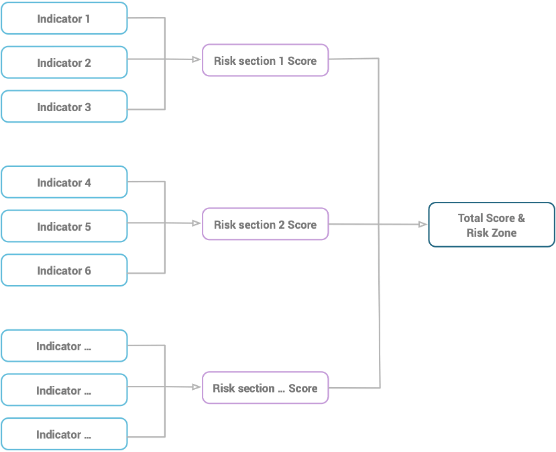

Each of the seven sections in the Sovereign Risk Scores includes several quantitative indicators (as shown in Table 1) to yield an initial score for each risk section. We then aggregate the seven risk sections—which are weighted to reflect their relative importance—to produce an overall risk score, which we finally map to the risk category and letter rating.

Figure 1 shows a schematic of this process.

The respective weights of each risk section are as follows:

| Risk Section | Section Weight |

|---|---|

| Economic growth prospects | 20% |

| Institutions and governance | 20% |

| Monetary stability | 10% |

| Fiscal solvency and public debt | 20% |

| Sovereign liquidity | 15% |

| External debt sustainability | 10% |

| Private sector strength | 5% |

Where no underlying indicators are available for a particular risk section, we distribute its weight between the other sections on a pro-rata basis to avoid the attendant risk of creating a downward bias in the overall risk assessment.

Quantitative assessment of indicators

We assess quantitative indicators by assigning values along a risk spectrum ranging from low to high. The risk spectrum is divided into several intervals and risk points are assigned to each interval. For example, higher quality of institutions and governance, such as the rule of law, indicates a greater likelihood that contracts can be enforced through the legal system. Therefore, in our framework, countries with a weaker rule of law receive more risk points than those with a stronger rule of law (see Table 4). For instance, where a country has a Rule of Law indicator rating of 25, we would assign it a score of 75 out of 100 risk points.

| Rule of Law | 0 < 40 | 40 < 50 | 50 < 60 | 60 < 70 | 70 < 80 | 80 < 100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk points | 100 | 80 | 60 | 40 | 20 | 0 |

Interaction term between solvency and liquidity

Based on previous economic and financial crises, we find that there is an important feedback mechanism between solvency and changes to the liquidity situation of a sovereign that can affect a sovereign credit risk assessment. The deterioration of a country’s fiscal and current account has a more significant impact on its ability and willingness to repay its sovereign debt where government debt ratio is already high. In other words, a country’s fiscal space depends on its starting condition (e.g. given debt ratios).

We reflect this feedback mechanism in the CountryRisk.io Sovereign Risk Scores. To do this, we take the standalone results of the “sovereign liquidity” and “fiscal solvency and public debt” risk sections as the basis of the calculation and map the two results to the respective tables shown below. For example, if the liquidity result of a country is 55 (which already signals a weak liquidity position), the liquidity adjustment factor is 7. If the solvency risk factor is 35 (which denotes a solid solvency position), the adjustment factor is 0.4. The total final adjustment factor is the product of both adjustment factors. In the given example: 7 x 0.4 = 2.8. Finally, we increase the final risk score by this number. The range of upward adjustment is between 0 and 10, or, in letter ratings, around two notches.

| Liquidity Section Result | 0 < 20 | 20 < 30 | 30 < 40 | 40 < 50 | 50 < 60 | 60 < 100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjustment factor | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 10 |

| Solvency Section Result | 0 < 30 | 30 < 40 | 40 < 50 | 50 < 60 | 60 < 100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjustment factor | 0 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1 |

Although this feedback mechanism leads to more variability of the risk scores over time, we find that this offers a useful reflection of market dynamics.

Adjustment for large economies

Large economies benefit from higher resilience to adverse international shocks than smaller ones, as their sizeable resources and more diverse, dynamic economies allow their governments to respond to such shocks more flexibly. Similarly, large economies have more bargaining power in multilateral organisations and forums that affords them a greater ability push through certain policies.

As a result, larger, more mature economies benefit from a downward adjustment of their CountryRisk.io Sovereign Risk Scores of up to 20 points, as shown in the mapping table below. To date, the US and, increasingly, China, have been the main beneficiaries of this adjustment.

| Share of Global Nominal GDP (USD) | 0 < 1% | 1% < 5% | 5% < 10% | 10% < 15% | 15% < 20% | 20% and above |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjustment factor | 0 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 10 | 20 |

Translating total risk points into risk categories

We convert each country’s total risk points as a share of maximum possible risk points into five category ratings ranging from “Very Low” to “Very High” sovereign credit risk. For instance, if the indicator assessments and their respective risk sections yield a total risk score of 35% (out of 100%), we map this score to the risk category of “Medium”. Table 8 summarises how we convert total risk points into a risk category. We also visually represent these ratings using a traffic light system with colours ranging from deep red to green.

It is important to note that there is no wholly objective way of determining the thresholds for each risk category. By and large, these are subjective decisions that should align with the organisation’s risk appetite. Classifying too many countries as “Very High Risk” would lead to highly restricted business activities, while classifying too many as “Very Low Risk” would lead to un-provisioned risk in the business’s portfolio.

| Risk Points Range | Risk Category | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 0 - 20 | Very Low | Very low risk that the government will not honour its foreign debt obligations. |

| 20 - 35 | Low | Low risk that the government will not honour its foreign debt obligations. |

| 35 - 47.5 | Medium | Some risk that the government will not honour its foreign debt obligations. |

| 47.5 - 62.5 | High | High risk that the government will default on its foreign currency debt obligations in the near future. |

| 62.5 - 100 | Very High | Very high risk that the government will default on its foreign currency debt obligations in the near future. |

Translating total risk points into letter ratings

We convert each country’s total risk points as a share of maximum possible risk points into the standard sovereign credit ratings ranging from AAA to CCC. The mapping table is shown below.

| Sovereign Risk Score Range | Letter Rating | Risk Level | Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | — | D | In Default | The country is currently in default on some or all of its obligations. |

| 60.00 | 62.49 | C | Speculative Grade | Very highly speculative credit quality and high default risk. Default can be avoided only in a favourable economic environment. |

| 57.50 | 59.99 | CC | ||

| 55.00 | 57.49 | CCC | ||

| 52.50 | 54.99 | B- | Speculative Grade | Highly speculative credit quality reflects elevated uncertainty about the country’s ability and willingness to repay its obligations. While current financial obligations are honoured, a deterioration of the economic environment, external account, indebtedness or heightened political uncertainty all have the potential to challenge the country’s capacity to honour its obligations. |

| 50.00 | 52.49 | B | ||

| 47.50 | 49.99 | B+ | ||

| 45.00 | 47.49 | BB- | Speculative Grade | Speculative credit quality reflects uncertainty about the country’s ability and willingness to repay its obligations. Issuer credit risk is vulnerable to unexpected changes. |

| 42.50 | 44.99 | BB | ||

| 40.00 | 42.49 | BB+ | ||

| 37.50 | 39.99 | BBB- | Investment Grade | Good credit quality reflects a low expected credit risk. Unexpected changes in the domestic or global economic environment or structural changes are more likely to impair the credit quality. |

| 35.00 | 37.49 | BBB | ||

| 32.50 | 34.99 | BBB+ | ||

| 30.00 | 32.49 | A- | Investment Grade | High credit quality with capacity and willingness to honour its obligations. That said, credit risk is susceptible to deterioration in the case of unexpected changes of the country’s fundamentals or its economic outlook. |

| 27.50 | 29.99 | A | ||

| 25.00 | 27.99 | A+ | ||

| 20.00 | 24.99 | AA- | Investment Grade | Very high credit quality with ample capacity and proven willingness to honour its obligations. Credit quality is only marginally weaker than the highest credit quality of AAA-rated issuers. |

| 15.00 | 19.99 | AA | ||

| 10.00 | 14.99 | AA+ | ||

| 0.00 | 9.99 | AAA | Investment Grade | Highest credit quality accorded to the greatest capacity and willingness to honour its obligations. Credit quality is unlikely to be weakened by foreseeable events. |

Governance process

- Update frequency: We update our Sovereign Risk Index and publish it on the CountryRisk.io Insights Platform towards the end of each month. In addition, we update the data on an ad hoc basis whenever substantial new information becomes available.

- Model review and adjustments: CountryRisk.io strives to continuously improve its methodology, such as by incorporating new high-quality indicators as and when they become available. CountryRisk.io also consults external experts to review the model and any adjustments we make to it. We will reflect any changes in future versions of this methodology document.