Methodology

Introduction

This document details the scope and methodology of CountryRisk.io’s rating process. Our goal remains simple: to bring greater transparency to sovereign government risk ratings, while explicitly integrating ESG factors into their underlying analysis.

Core beliefs and guiding principles

CountryRisk.io’s core belief is that sovereign ratings are a public good.

Our guiding principles include:

Independence: CountryRisk.io is independent of any rating issuer or commercial credit rating agency.

Transparency: CountryRisk.io pursues absolute transparency in its models and processes.

Structured framework: CountryRisk.io believes that a structured framework combining quantitative and qualitative factors is the best way to analyse sovereign and country risk.

Constructive exchange: CountryRisk.io believes that a constructive exchange of perspectives improves country risk analysis and, therefore, that multiple informed country risk views are superior to one.

ESG as the new standard

CountryRisk.io has long incorporated Governance indicators into its sovereign risk framework, such as the rule of law, control of corruption, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, voice & accountability and political stability. In this regard, CountryRisk.io does not differ from other models whose frameworks also incorporate these indicators.

Meanwhile, the practice of incorporating Environmental and Social indicators into sovereign ratings, alongside existing Governance indicators to achieve comprehensive ESG integration, is evolving rapidly. Furthermore, the number of indicators in each of these areas is increasing to capture a growing range of risk factors. This expansion began with the addition of climate change as an Environmental risk factor, a category that has since extended to include many other factors relevant to sovereign ratings, such as biodiversity loss. At the same time, social factors, such as equality and inclusion, have also become more commonplace. With such fast-paced change that looks set to continue for the foreseeable future, a standard methodology for ESG integration has, therefore, yet to emerge.

Nevertheless, CountryRisk.io's model also includes several metrics for the Social and Environmental pillars. Specifically, we include forward-looking qualitative assessments with regard to governments’ policy commitments, as well as the general acceptance of the need for sustainability in the public and private sectors. One example relates to climate change, where we ask analysts to assess governments’ overall commitment to and effectiveness in reducing national emissions, as well as their chances of hitting their targets by 2030. Although such questions tend to be best answered with reference to thorough knowledge of governmental policies, we believe that the judgment of individual analysts based upon their own experience may be just as revealing.

Since debt sustainability analysis is a forward-looking tool that helps in assessing a sovereign’s probability of default given long-term assumptions for growth, inflation, total debt and interest rates, we found it appropriate to include explicitly fundamental drivers of long-term growth. Demographics, human capital and education, infrastructure, exposure to natural disasters, natural resource endowment and access to technology have always been part of our model’s section on economic and growth prospects.

By the same token, it was also natural for us to include within our debt sustainability framework qualitative indicators of issues that could give rise to uncertainties in the baseline scenario and undermine its results. Unanticipated events, such as financial crises, pandemics and natural disasters, may increase fiscal risks arising from policy interventions designed to mitigate the attendant social and economic hardship. The financial crisis of 2007/2008 and the ensuing European sovereign debt crisis were high-impact events that severely impaired government finances in many economies, advanced and emerging alike. Appropriately incorporating such scenarios into our rating platform not only reduces the likelihood of frequent changes to ratings, but also sets our rating framework apart from credit rating agencies who are, in one way or another, constrained from issuing immediate changes to ratings when warranted.

Another integral part of CountryRisk.io's analytical framework is a section dedicated to political stability. Its components, relevant to Social factors, include impetus for economic unrest, ethnic strife and religious conflict. One example of an event brought on by factors that called into question countries’ democracy, quality of institutions and long-term growth prospects was the Arab Spring; an impressive demonstration of citizens’ deep-seated frustration and dissatisfaction over economic decline, growing inequality, corruption, political repression and failing infrastructure and social services, among others.

In October 2018, CountryRisk.io released a separate rating platform to generate country and sovereign risk ratings that explicitly account for Environmental and Social factors. Although the model was independent of the standard sovereign risk model, it shared the same objective—assessing the willingness and ability of governments to repay their debt obligations—and the same methodological approach. We find that incorporating such risk factors alongside traditional ones (e.g. economic growth prospects, fiscal and public debt, balance of payment flexibility) captures a more nuanced and comprehensive view of a country. ESG risk sections have a combined weight of 30% in our model.

The consequences of weather-related disasters, fragmented institutions or weak social cohesion are factors that could reduce a government’s ability or willingness to honour its sovereign debt obligations. Since the associated costs of environmental and social risk factors, whether direct (e.g. loss of capital or economic output) or indirect (e.g. migration), can be large enough to severely impact an economy, integrating ESG risk drivers into country and sovereign risk assessments is extremely useful.

Moreover, such integration is especially valuable for better credit differentiation among the least developed countries, where factors like the quality of the education and health systems or vulnerability to environmental risks add more granular information. By contrast, such factors could lead to smaller changes—if any—among the highest-rated countries.

Thus, despite many arguments 1 against the systematic integration of ESG factors, we decided to merge both platforms and make the ESG sovereign risk model our standard. Doing so reflects our firm conviction that ESG factors will only become harder to disregard and increasingly vital to analysing the probability of sovereign default.

1 The lack of standardisation in explaining what constitutes material ESG factors is just one of many arguments against systematically incorporating such factors in sovereign risk analysis. Other challenges include data issues, such as reporting frequency, availability and measurement consistency, and other statistical problems.

Overview

CountryRisk.io focuses strictly on rating sovereign governments at a national level. Regional governments and quasi-sovereign entities lie outside of our scope, although we consider such entities’ commitments when we assess central governments’ obligations.

We define a credit rating as an assessment of a sovereign’s probability of default and/or the likelihood that it will fail to honour its obligations to commercial creditors on time. The criteria we use to assess a central government’s willingness and ability to meet its debt obligations consist of a broad range of statistically determined indicators commonly cited in the literature on sovereign and country risk analysis.

In addition to quantitative economic and financial indicators, we augment our analysis with selected qualitative indicators. Since quantitative measures do not always capture current or potential risks in their entirety, we believe this approach yields a more comprehensive risk analysis. One such qualitative measure considers policymakers’ independence; specifically, the extent to which they can implement monetary policies that maintain price stability without government interference. While it may appear that central banks generally enjoy independence, periods of economic stress or instability may put their autonomy to the test. Although deciding how likely it is that a central bank will maintain its independence during difficult times is a qualitative judgement and, therefore, somewhat subjective, we believe it is highly relevant to assessing country risk.

CountryRisk.io emphasises the sovereign’s structural characteristics and fundamentals, reflecting a through-the-cycle perspective rather than focusing on cyclical or short-term views. This approach precludes frequent rating fluctuations, although an ensuing revision may be warranted if a sovereign undergoes significant changes that were unforeseen during the previous review.

We strive to rate a wide range of sovereigns and apply the same rating framework to all countries. Our ESG sovereign rating methodology does not differentiate among economies based on their stage of economic development; that is, we generally assess all developed countries, emerging markets and frontier economies according to the same framework. Similarly, we apply the same methodology regardless of the size of a nation and its economy. However, we exempt from external liquidity assessments those countries whose currencies are classified as a reserve currency or are frequently traded in the global foreign exchange markets.

Sovereign versus country risk

Although the terms are often used interchangeably, it is useful to distinguish between sovereign and country risk since they measure different things. We define sovereign risk as the probability that a national government will default on its debt obligations. Meanwhile, country risk includes transfer and convertibility (T&C) risk. This represents the likelihood of the government imposing capital and exchange controls that would impede the ability of its non-sovereign sector to convert local currency into foreign currency, thereby inhibiting the ability of those borrowers to honour their obligations to foreign creditors. Transfer risk also includes forces majeures, such as wars, expropriations, revolutions, civil disturbances and natural disasters.

Until recently, country risk had a broader focus than sovereign risk. But in 2011, following the large-scale transfers and government financial support in response to the global financial and sovereign debt crisis, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) called for a more extensive definition of sovereign risk. Our holistic approach to sovereign risk analysis is consistent with the IMF’s recommendations. CountryRisk.io integrates macroeconomic fundamentals with elements that incorporate broader balance sheet developments, debt portfolio structures, portfolio and equity investors, cross-border linkages and the country’s financial assets, along with environmental and social indicators that we believe to be material.

Foreign versus local currency ratings

Our ESG sovereign risk ratings include sub-ratings for both local currency (LCY) and foreign currency (FCY) risks. These ratings indicate the sovereign’s ability and willingness to meet its debt obligations in its local (domestic) currency and foreign currencies, respectively. While this distinction in credit quality has narrowed over the last decade, we believe differences remain that still warrant separate ratings.

In recent years, many sovereigns, particularly those with emerging economies, have significantly deepened and broadened their domestic capital markets and liberalised their current and capital accounts—characteristics that have not always defined such economies. As a result, it was often easy to distinguish between LCY and FCY risk ratings. Now, in several emerging markets, significant reforms to their domestic capital markets and balance of payments status have yielded rating upgrades. At the same time, these developments have also narrowed or eliminated the former gaps between LCY and FCY risk ratings.

Some observers have argued that separate ratings for local and foreign currency risk are no longer necessary. However, since emerging and developed economies continue to exhibit inconsistencies—some quite significant—in fiscal, debt and monetary policies, we believe that a distinction between these ratings is still justified. External account improvements do not necessarily imply flexibility in fiscal accounts. A government’s ability to improve its tax policies or exert influence on monetary policy via the money supply is, in our view, very likely to perpetuate the gap in the LCY and FCY ratings.

Data

CountryRisk.io utilises primary data from national sources, including international and regional multilateral institutions, both for our standard country rating model as well as for our sovereign ESG framework.

In particular, as the leading organisation in promoting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the United Nations is a key source of ESG data. We also source data from other specialised sources for various indicators, such as environmental vulnerability.

CountryRisk.io provides users with datasets for a wide range of countries. Users can also upload and share their own datasets, which allows them to reflect their views on the best available historical data and forecasts. Our platform also facilitates a constructive exchange among users regarding the quality and materiality of the data used in rating analyses. Our community features ensure that users can quickly raise and address data quality concerns.

Methodology

CountryRisk.io uses a hybrid credit risk assessment model that combines statistical and heuristic elements. Heuristic models derive insights from practical experience, which can capture risk factors that quantitative data or statistical models cannot.

In contrast to heuristic models that rely on subjective experience, statistical models apply quantitative methods to establish relationships between certain factors—for example, the public debt-to-GDP ratio—and country credit risk. Such models have the advantage of reducing biases, which makes them useful for back-testing. However, it should be noted that statistical models are also vulnerable to biases that can influence the process of selecting, specifying and calibrating the model.

We review our rating model annually, taking into account the latest developments and feedback from an expert panel and the CountryRisk.io community.

Foreign and local currency rating

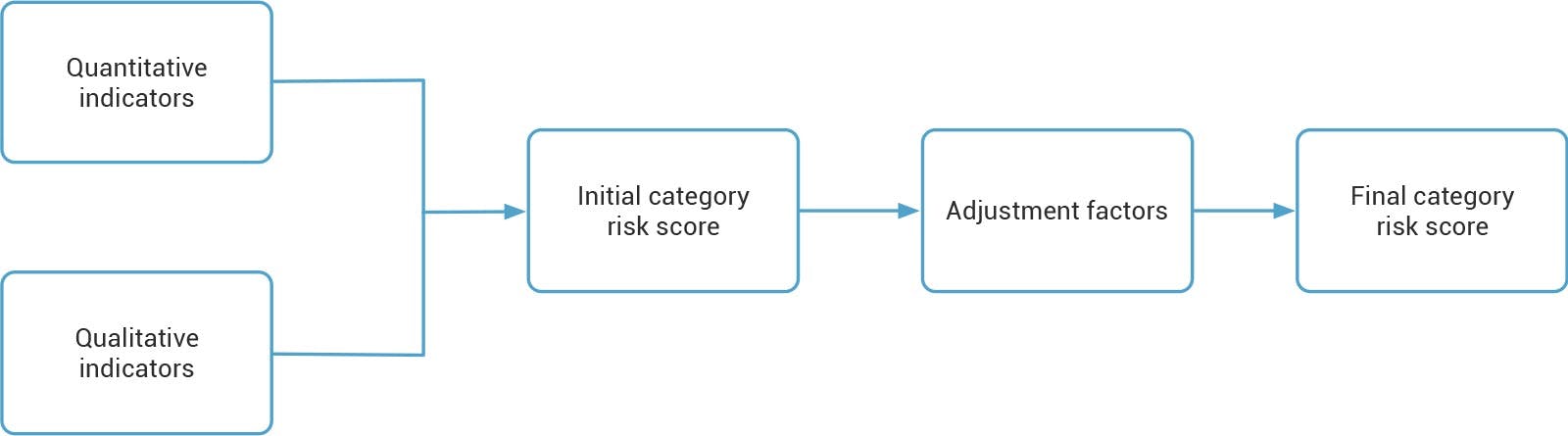

CountryRisk.io’s ESG rating model employs thirteen risk categories that we use to derive the FCY and LCY ratings. Each category includes a broad range of quantitative and qualitative indicator assessments, which together yield an initial category risk score. We also embed adjustment factors into each risk category that can either increase or decrease its risk score. The adjustment factors help the analyst produce a thorough, nuanced analysis. A simplified schematic of the process is shown in Figure 1 below.

Each category receives a risk score of between 0% and 100%. We then aggregate all 13 risk categories, each of which is weighted according to its relative importance, to yield an overall sovereign risk score. The categories and respective weights are as follows:

| Category | FCY Weight | LCY Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Economic growth prospects | 12.5% | 12.5% |

| Political stability | 5% | 12.5% |

| Institutions and governance | 10% | 12.5% |

| Monetary stability | 5% | 10% |

| Banking sector strength | 5% | 5% |

| Fiscal account vulnerability | 12.5% | 7.5% |

| Public debt sustainability | 12.5% | 7.5% |

| Balance of payment flexibility | 10% | 7.5% |

| External debt sustainability | 7.5% | 5% |

| Climate change & renewable energy | 5% | 5% |

| Biodiversity | 5% | 5% |

| Health, Food & Poverty | 5% | 5% |

| Labour market, social safety nets & equality | 5% | 5% |

Quantitative assessment of indicators

We assess quantitative indicators by assigning values in a risk spectrum ranging from low to high. The risk spectrum is divided into several intervals, and risk points are assigned to the individual intervals. For example, a relatively high GDP per capita indicates a higher level of economic development and receives a lower country credit risk score. Hence, in our framework, countries with lower GDPs per capita receive more risk points than those with higher GDPs per capita (see Table 2).

The mapping of indicator values to risk points is not necessarily linear, which means that risk points for most indicators increase exponentially as the indicator weakens.

| GDP per capita (USD) | < 2000 | 2000 < 5000 | 5000 < 10000 | 10000 < 15000 | 15000 < 25000 | 25000 < 30000 | ≥ 30000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk points | 40 | 30 | 20 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 0 |

For some other indicators, a very high or very low value translates into higher risk points. For instance, a country with very high consumer price increases (hyperinflation) receives high risk points, but one with sharp consumer price declines (deflation) also receives risk points. Countries that receive the lowest risk point scores have annual consumer prices increases of between 0% and 3%.

| Inflation rate (5 year average) | < -5% | -5% < 0% | 0% < 3% | 3% < 5% | 5% < 10% | ≥ 10% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk points | 10 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 20 |

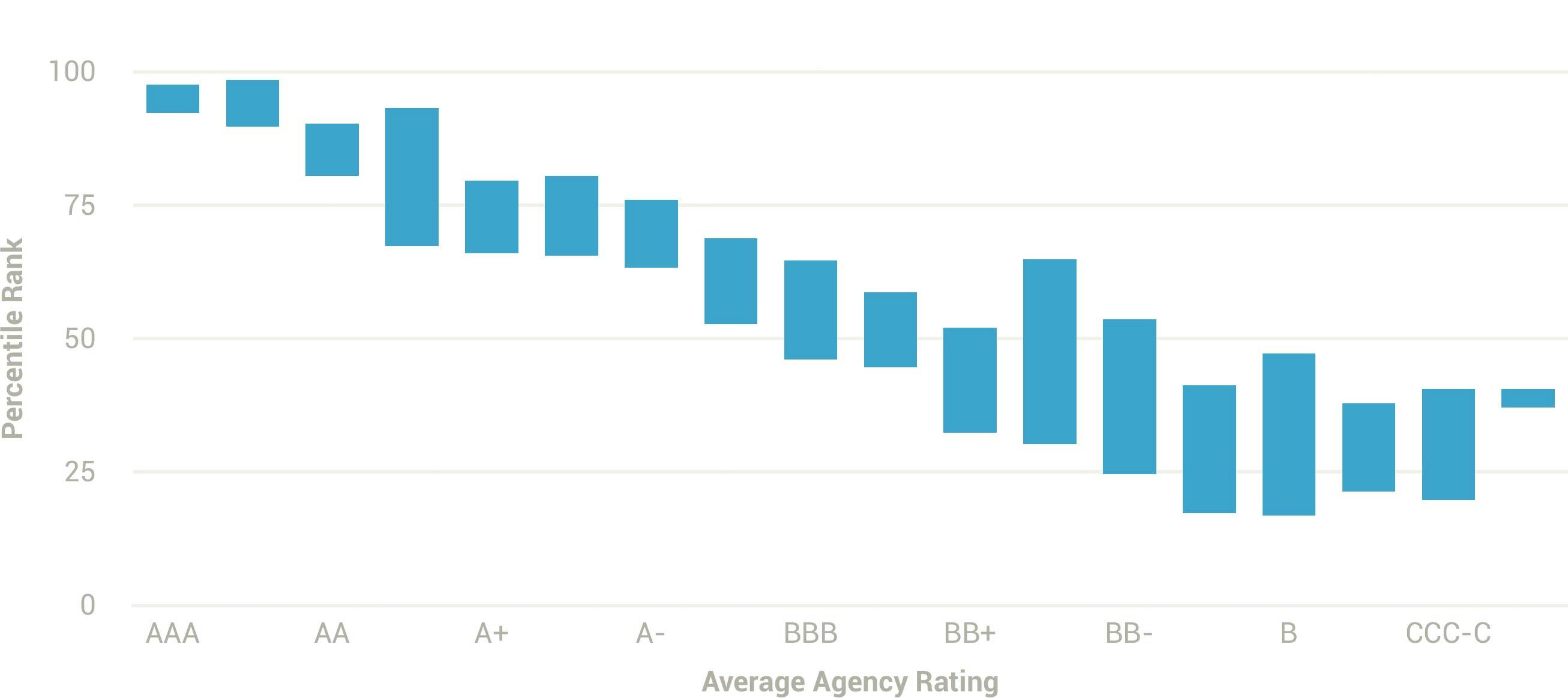

We derived our risk intervals from the economic literature, research and statistical analysis. We also compare our risk intervals by grouping them according to the average ratings from S&P, Moody's and FitchRatings.

Figure 2 above shows a boxplot (25 and 75 percentiles) of the corruption indicator, grouped by rating. We sourced the data from the World Bank and expressed it in percentile ranks. For example, countries that S&P, Moody's and FitchRatings rated AAA on average have ratings between 92.3 and 97.6, with a median of 95.2. This is based on annual records since the World Bank initiated this indicator in 1996. Table 4 shows the historical distribution of the indicator per rating.

| Letter | Mean | Median | 25% Percentile | 75% Percentile | 5% Percentile | 95% Percentile | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAA | 94.6 | 95.2 | 92.3 | 97.6 | 86.1 | 100.0 | 149 |

| AA+ | 93.8 | 95.1 | 89.8 | 98.5 | 85.3 | 99.5 | 38 |

| AA | 83.6 | 84.6 | 80.5 | 90.2 | 65.8 | 95.2 | 46 |

| AA- | 79.7 | 82.6 | 67.3 | 93.2 | 57.5 | 98.5 | 34 |

| A+ | 69.6 | 71.8 | 66.0 | 79.6 | 33.0 | 86.2 | 49 |

| A | 72.1 | 72.0 | 65.6 | 80.5 | 46.3 | 90.9 | 50 |

| A- | 68.9 | 70.2 | 63.3 | 76.0 | 40.3 | 87.9 | 43 |

| BBB+ | 59.3 | 61.5 | 52.7 | 68.8 | 16.6 | 88.6 | 34 |

| BBB | 51.1 | 54.1 | 46.1 | 64.6 | 13.1 | 73.1 | 47 |

| BBB- | 49.7 | 52.2 | 44.6 | 58.7 | 12.6 | 68.3 | 56 |

| BB+ | 44.1 | 43.9 | 32.4 | 52.1 | 12.6 | 84.8 | 59 |

| BB | 46.7 | 50.5 | 30.2 | 64.9 | 15.5 | 74.8 | 38 |

| BB- | 38.2 | 33.6 | 24.6 | 53.7 | 11.7 | 84.1 | 44 |

| B+ | 31.8 | 31.3 | 17.3 | 41.3 | 4.6 | 74.4 | 36 |

| B | 33.3 | 29.2 | 16.9 | 47.2 | 8.0 | 71.6 | 37 |

| B- | 30.6 | 28.5 | 21.3 | 37.9 | 15.1 | 44.5 | 30 |

| CCC-C | 29.7 | 22.9 | 19.8 | 40.6 | 15.6 | 55.9 | 8 |

| DDD-SD | 37.2 | 39.5 | 37.1 | 40.6 | 18.5 | 41.7 | 9 |

We defined all indicator assessments on a stand-alone basis. This means that the mapping table of an indicator value to risk points ignores how a country scores on other indicators.

Every indicator that we mapped into risk intervals is de-trended and stationarised by taking meaningful ratios (e.g., external debt-to-GDP), calculating growth rates or evaluating on a real (inflation-adjusted) basis to yield a meaningful comparison over time.

Translating total risk points into FCY and LCY letter ratings

CountryRisk.io follows the standard practice of representing risk ratings using letters, ranging from AAA for the lowest-risk countries to C for the highest-risk countries. Countries currently in default on some or all of their obligations, which we define as having missed interest and/or principal payments, receive the rating D. Table 5 summarises how we translate total risk points into a letter rating. A rating analysis that yields an overall risk score of 88%, for example, is given a letter rating of CC.

| FYC Risk Points Range | Letter Rating | Risk Level | Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | — | D | In Default | The country is currently in default on some or all of its obligations. |

| 100.00 | 90.00 | C | Speculative Grade | Very highly speculative credit quality and high default risk. Default can be avoided only in a favourable economic environment. |

| 89.99 | 85.00 | CC | ||

| 84.99 | 80.00 | CCC | ||

| 79.99 | 75.00 | B- | Speculative Grade | Highly speculative credit quality reflects elevated uncertainty about the country’s ability and willingness to repay its obligations. While current financial obligations are honoured, a deterioration of the economic environment, external account, indebtedness or heightened political uncertainty all have the potential to challenge the country’s capacity to honour its obligations. |

| 74.99 | 70.00 | B | ||

| 69.99 | 65.00 | B+ | ||

| 64.99 | 60.00 | BB- | Speculative Grade | Speculative credit quality reflects uncertainty about the country’s ability and willingness to repay its obligations. Issuer credit risk is vulnerable to unexpected changes. |

| 59.99 | 55.00 | BB | ||

| 54.99 | 50.00 | BB+ | ||

| 49.99 | 45.00 | BBB- | Investment Grade | Good credit quality reflects a low expected credit risk. Unexpected changes in the domestic or global economic environment or structural changes are more likely to impair the credit quality. |

| 44.99 | 40.00 | BBB | ||

| 39.99 | 35.00 | BBB+ | ||

| 34.99 | 30.00 | A- | Investment Grade | High credit quality with capacity and willingness to honour its obligations. That said, credit risk is susceptible to deterioration in the case of unexpected changes of the country’s fundamentals or its economic outlook. |

| 29.99 | 25.00 | A | ||

| 24.99 | 20.00 | A+ | ||

| 19.99 | 15.00 | AA- | Investment Grade | Very high credit quality with ample capacity and proven willingness to honour its obligations. Credit quality is only marginally weaker than the highest credit quality of AAA-rated issuers. |

| 14.99 | 10.00 | AA | ||

| 9.99 | 5.00 | AA+ | ||

| 4.99 | 0.00 | AAA | Investment Grade | Highest credit quality accorded to the greatest capacity and willingness to honour its obligations. Credit quality is unlikely to be weakened by foreseeable events. |

| LYC Risk Points Range | Letter Rating | Risk Level | Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | — | D | In Default | The country is currently in default on some or all of its obligations. |

| 100.00 | 92.50 | C | Speculative Grade | Very highly speculative credit quality and high default risk. Default can be avoided only in a favourable economic environment. |

| 92.49 | 87.50 | CC | ||

| 87.49 | 82.50 | CCC | ||

| 82.49 | 77.50 | B- | Speculative Grade | Highly speculative credit quality reflects elevated uncertainty about the country’s ability and willingness to repay its obligations. While current financial obligations are honoured, a deterioration of the economic environment, external account, indebtedness or heightened political uncertainty all have the potential to challenge the country’s capacity to honour its obligations. |

| 77.49 | 72.50 | B | ||

| 72.49 | 67.50 | B+ | ||

| 67.49 | 62.50 | BB- | Speculative Grade | Speculative credit quality reflects uncertainty about the country’s ability and willingness to repay its obligations. Issuer credit risk is vulnerable to unexpected changes. |

| 62.49 | 57.50 | BB | ||

| 57.49 | 52.50 | BB+ | ||

| 52.49 | 47.50 | BBB- | Investment Grade | Good credit quality reflects a low expected credit risk. Unexpected changes in the domestic or global economic environment or structural changes are more likely to impair the credit quality. |

| 47.49 | 42.50 | BBB | ||

| 42.49 | 37.50 | BBB+ | ||

| 37.49 | 32.50 | A- | Investment Grade | High credit quality with capacity and willingness to honour its obligations. That said, credit risk is susceptible to deterioration in the case of unexpected changes of the country’s fundamentals or its economic outlook. |

| 32.49 | 27.50 | A | ||

| 27.49 | 22.50 | A+ | ||

| 22.49 | 17.50 | AA- | Investment Grade | Very high credit quality with ample capacity and proven willingness to honour its obligations. Credit quality is only marginally weaker than the highest credit quality of AAA-rated issuers. |

| 17.49 | 12.50 | AA | ||

| 12.49 | 7.50 | AA+ | ||

| 7.49 | 0.00 | AAA | Investment Grade | Highest credit quality accorded to the greatest capacity and willingness to honour its obligations. Credit quality is unlikely to be weakened by foreseeable events. |

Translating total risk points into Transfer and Convertibility (T&C) risk ratings

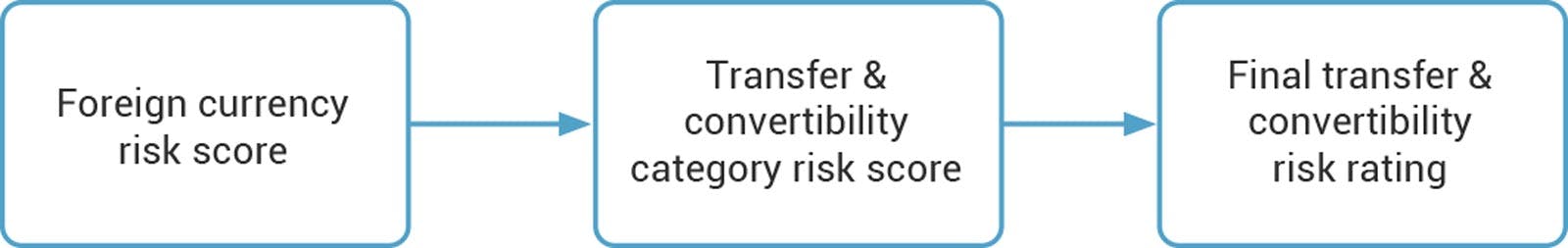

A country’s foreign currency sovereign risk rating, derived from our sovereign risk framework, serves as the basis for determining a country’s T&C Risk. A simplified schematic of the process is shown in Figure 3.

We use a series of qualitative questions to determine the T&C category risk score, which ranges between 0% and -15% and is added to the foreign currency risk score. As a result, the T&C category risk score can also be understood as a rating upgrade from the foreign currency rating. Here, we assume that capital and exchange controls become more likely as the probability of a sovereign default increases, which would probably lead to shortfalls in foreign exchange reserves.

The final T&C risk score yields a T&C risk rating, which we use to assign the country to one of seven incremental risk buckets. Table 6 shows the T&C Risk ratings we may give to a country, their interpretations and related T&C risk point ranges.

| T&C Risk Points Range | Risk Rating | Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 15 | 0 | The probability that the government will impose capital or exchange controls is negligible. |

| 15 | 30 | 1 | The probability that the government will impose capital or exchange controls is very unlikely. |

| 30 | 45 | 2 | The probability that the government will impose capital or exchange controls is somewhat unlikely. |

| 45 | 60 | 3 | The probability that the government will impose capital or exchange controls is moderate. |

| 60 | 75 | 4 | The probability that the government will impose capital or exchange controls is somewhat likely in the event of a default. |

| 75 | 90 | 5 | The probability that the government will impose capital or exchange controls is very likely in the event of a default. |

| 90 | 100 | 6 | The probability that the government will impose capital or exchange controls is almost certain. |

Risk Categories

Economic structure and growth prospects

A country’s economic structure is a key determinant of its risk level. The structure of the country's economy influences its growth prospects and resilience, which, in turn, determine its flexibility to generate sustainable revenues and service the government’s obligations.

To assess a country’s economic prospects, we analyse its historical and current growth trends, as well as its fundamental long-term growth drivers such as human capital, integration with the global economy and technological resources. An economy with a high GDP per capita or favourable growth outlook is more likely to provide the government with stable tax revenues. Conversely, a country with limited prospects for increasing the per capita income of its citizens will likely experience persistent revenue shortfalls and, therefore, need to borrow regularly— either in its domestic capital markets or abroad—to bridge the inevitable deficits.

A key task of governments is to provide education to their citizens, including schools and universities, apprenticeship programs and basic research and development. High-quality education fosters human capital and enables citizens to switch between professions as required. Education also tends to be an important determinant of social cohesion. Learning is a lifelong activity facilitated by new technologies and has significant potential to reduce the risk of parts of society being left behind.

Diversity is also an important aspect of an economy’s structure. A country that relies heavily on a single sector, like agriculture, is vulnerable to shocks brought on by externalities such as poor weather or reduced international demand. This is also true for economies that rely on commodity exports that depend on the global growth cycle. Similarly, we believe that countries with overvalued currencies effectively overstate their GDP per capita, which creates misperceptions surrounding their capacity to generate revenues. A rapid increase in credit growth that outpaces real GDP growth will eventually lead an economy with an overvalued currency to a marked downturn as its credit bubble bursts.

| Indicators | Adjustment Factors |

|---|---|

| Income level | Size of the economy |

| Real GDP growth volatility | Diversity in economic structure |

| Fundamental growth driver: Demographics | Role of credit |

| Fundamental growth driver: Human capital and education | Currency valuation impact on per capita GDP |

| Fundamental growth driver: Infrastructure | Exposure to natural disasters |

| Fundamental growth driver: Access to technology | |

| Fundamental growth driver: Integration with the world economy | |

| Fundamental growth driver: Savings |

Political stability

A country’s political environment is fundamental to CountryRisk.io’s analysis of risk, and we assess this factor primarily using qualitative indicators. A nation's system of government typically indicates its ability to create and implement policies conducive to stable growth and healthy public finances. Democratic countries allow for checks and balances among its branches, which help ensure a relatively unbiased representation of its citizens’ concerns. In contrast, a dictatorship mainly serves the rent-seeking interests of a tiny fraction of society at the expense of the majority.

We also assess social factors—such as religious or ethnic divisions, economic incentives for social unrest and the military’s role in politics—and weigh their relevance for a country’s economic prospects. Ethnic or religious conflicts could lead to political instability or even civil war. Studies show that, in general, the potential for religious or ethnic conflict is highest in countries populated primarily by two ideologically opposed groups, while more diverse societies appear less likely to experience destabilising and destructive unrest. Studies also suggest that economic incentives for rebellion are more likely in countries that generate a considerable share of income—at least 20%—through the export of primary commodities.

In most cases, an active military presence in a country’s politics is destabilising. A history of civil war or external conflict is also an important consideration, since the root causes of such hostilities often persist even after the conflict ends. This increases the risk of renewed conflict, with the probability falling only marginally each year. Usually marked by the destruction of human, private and public capital, violent conflicts can hobble economic growth. When severe and prolonged, such conflicts are likely to damage an economy for years, undercutting the government’s ability to implement policies favourable to growth.

| Indicators | Adjustment Factors |

|---|---|

| Quality of democracy | Probability of change in government |

| History of civil war or external conflict | |

| Religious conflict | |

| Ethnic strife | |

| Impetus for social unrest | |

| Influence of the military |

Institutions and governance

Robust political institutions serve to anchor a country during times of economic instability and mitigate concerns that a government might not service its debt. Countries with a robust legal system, established mechanisms for fighting corruption, an effective government, a healthy regulatory regime and political stability and transparency receive lower risk scores in our framework. In addition, this risk category includes an indicator that assesses the overall ease of doing business.

| Indicators | Adjustment Factors |

|---|---|

| Rule of law | Frequency of internet shutdowns |

| Control of corruption | Natural resources |

| Government effectiveness | |

| Regulatory quality | |

| Voice and accountability | |

| Political stability | |

| Transparency | |

| Respect for human rights | |

| Ease of doing business |

Monetary policy

Sound monetary policy is a foundation for stable growth and reduces the risk of economic fluctuations during periods of stress. This indicator assesses the ability of monetary authorities to use tools at their disposal flexibly and independently, without interference from governments whose goals may not align with those of the central bank.

A growing number of central banks in advanced and emerging economies identify price stability as their primary monetary objective. Thus, a stable inflationary environment indicates the authorities’ ability to achieve that goal. This is important as it minimises risks in related channels, such as the banking and financial sector as well as the exchange rate for its currency.

Other central banks choose to target a stable exchange rate or allow its currency to fluctuate against a reference currency or basket of currencies. While a steady exchange rate is a legitimate goal for a central bank, it also means that monetary authorities lose considerable flexibility in using various tools that might become crucial when the exchange rate undergoes a speculative attack. In such an environment, the central bank could take several actions to defend the exchange rate, although such actions might also stifle growth. Alternatively, in an extreme response, the central bank could abandon its objective when foreign reserves are depleted or successive interest rate hikes unacceptably burden the economy.

A credible monetary policy and a solid track record for policymakers go a long way to ensuring stable inflation trends and growth in the money supply that are consistent with the economy’s expansion. They also keep real interest rates in check which, if they reach very high levels, are a sure precursor to a banking and financial crisis. The credibility issue becomes particularly important during crisis periods, when authorities may undertake exceptional temporary monetary measures to stabilise the economy. As necessary as these measures may be in the moment, it is ultimately the central bank’s ability to wind them down at the appropriate time that ensures a lasting recovery.

One of the key adjustment factors in this risk assessment category includes the level and persistence of deflation, if any. While falling prices in themselves are not necessarily bad—for example, when they result from technological advances or improved productivity—an economy is at risk when aggregate demand falls significantly faster than aggregate supply, causing prices to spiral downward. The degree of dollarisation is another adjustment factor here. Studies show that when dollarisation reaches roughly 60% of deposits, macroeconomic stability can be jeopardised in countries that lack sufficiently robust institutional, monetary and fiscal foundations.

The 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent European sovereign debt crisis have prompted a reassessment of the links between the financial & public sectors and sovereign risk. While membership in a monetary union provides an anchor, its member countries may not all be synchronised in terms of core monetary (credit, prices and wages) and fiscal variables.

CountryRisk.io considers membership in a monetary union as a key adjustment factor and assesses whether each member country’s core monetary indicators are in line with those of other members. We also consider any potential risks that could spill over to other sectors in the economy.

Finally, we examine a country’s domestic financial market for possible sources of risk, whether from weak monetary policy or insufficient market development. We also look at the size and depth of local bond and equity markets, as they reflect the public and private sectors’ ability to raise funds at market-determined rates with transparent pricing.

The investor base in the local currency debt market is also important. A high proportion of foreign investors in the local currency debt market is common in the larger developed economies of the US, Japan, the UK and Germany. But the issue becomes critical for emerging market countries, whose markets are still shallow and often have restrictions in their current or capital accounts as well as inflexible exchange rate regimes.

| Indicators | Adjustment Factors |

|---|---|

| Consumer price development | Money supply growth |

| Inflation volatility | Degree of dollarisation |

| Growth in domestic credit | Membership in a monetary union |

| Real interest rate | Effectiveness of monetary policy via financial and capital markets |

| Exchange rate regime and integrity of monetary policy |

Banking sector strength

A strong and stable banking sector is important for efficient capital allocation to finance sustainable economic growth. History shows us that banking sector crises tend to result in significant economic output losses, lower growth prospects and considerable deterioration in sovereign credit quality due to contingent liabilities.

CountryRisk.io assesses the banking sector’s strength and its risks to the sovereign by following the CAMELS approach:

- Capital adequacy: The recent banking crises, particularly in advanced economies, added weight to the argument that more stringent capital requirements strengthen a banking system’s stability, improve the efficiency of intermediation and reduce corruption in lending. The active use of capital buffers is prudent to protect depositors and creditors during periods of financial stress. We encourage analysts to assess the sovereign’s regulations on the amount of capital a bank must hold and whether banks are required to identify the sources of funds counted as regulatory capital.

- Asset quality: Asset quality is one of the most critical determinants of banks’ overall health and, by extension, a sovereign’s entire banking sector. A bank’s loan portfolio and how it extends loans to borrowers are primary elements of a bank’s overall asset quality. Loans typically comprise the majority of a bank's assets and carry most of its capital risk. Securities may also constitute a large portion of a bank’s assets and also contain a significant share of its overall risk. The key indicator to monitor here is the ratio of non-performing loans to total loans.

- Management quality: This parameter assesses both the board of directors’ and management’s ability to identify, monitor, control and mitigate the risks stemming from the bank’s activities. Sound operations and full regulatory compliance are the focus here. The key areas include credit, market, liquidity, operational, legal, compliance and reputational risks.

- Earnings: The ability to earn sustainable returns on assets determines the viability of any business. For banks, core earnings are critical, as are its long-term earnings ability after discounting one-off events or fluctuations in net income. We encourage analysts to assess the quality and composition of earnings. Key ratios to watch are the trends and levels of the banking sector’s return on equity (ROE) and return on assets (ROA).

- Liquidity and funding: An assessment of the banking system’s funding structure and liquidity helps to identify potential liquidity vulnerabilities in times of stress. Liquidity risk is the current and prospective risk to a bank’s earnings or capital arising from its inability to meet its obligations without incurring unacceptable losses. The loan-to-deposit ratio is a key indicator to monitor here. In addition, structural liquidity mismatches in banks’ balance sheets—reflecting their portion of long-term, non-liquid assets (structural positions) financed with short-term funding and non-core deposits—are all sources of systemic risk.

- Sensitivity to market risk: This parameter measures the degree to which changes in market-based “prices” can reduce the banking sector’s earnings or economic capital. These include interest rates, foreign exchange rates, commodity prices or equity prices. Since little data is available for this factor, we encourage analysts to use the World Bank database on Bank Regulation and Supervision. We would specifically draw their attention to the regulatory restrictions the banking sector faces in securities activities.

As with the other parameters in our rating framework, CountryRisk.io allows adjustment to these areas to express a comprehensive, nuanced view on the strength of a banking sector. These include assessments on loan concentration and related-party lending. We also consider potential contingent liabilities to the government in terms of its ability to support banks in difficult times, which is ultimately dictated by its fiscal strength.

There are several potential sources of funding to assure liquidity during times of stress, including liquidity facility arrangements with international institutions or central banks. Access to deep domestic capital markets is another potential funding route, providing financing flexibility to the banking sector and reducing its reliance on foreign capital for funding. CountryRisk.io ascribes great importance to assessing currency and maturity mismatches, as these can quickly render banks vulnerable to liquidity and solvency risks when market liquidity in domestic and reserve currencies evaporate.

If banks commit similar mismatches across the board, an external shock—such as a sudden reversal in capital flows—could endanger the entire financial system. The 2008 global financial crisis underscored the gravity of maturity mismatches not only in emerging market economies, but also in those of developed markets. In emerging market economies with foreign currency liabilities, maturity mismatches create a more serious systemic risk, since currency mismatches invariably accompany them.

We also use several factors to assess the regulatory environment. These include:

- accounting and risk reporting standards;

- classification of loans;

- provisioning for loan losses;

- bankruptcy code and workout programs; and

- deposit insurance schemes.

While information may be available on the relevant regulator's website, the IMF Article IV Reports and the World Bank's database on banking regulation also provide general guidance in assessing these parameters. In addition, regulatory bodies’ historical efforts to enforce rules that discipline problematic institutions should also be taken into account. This record allows the analyst to gauge how willing regulators are to preserve a stable financial environment.

Finally, CountryRisk.io assesses potential risks stemming from shadow banking activities.

| Indicators | Adjustment Factors |

|---|---|

| Capital adequacy | Access to funding |

| Asset quality | Asset / liability matching |

| Management quality | Related party lending |

| Earnings and profitability | Shadow banking |

| Liquidity | Regulation and supervision |

| Sensitivity to market risk |

Fiscal account vulnerability

The sustainability of a sovereign’s fiscal deficits and debt is central to determining country risk. In assessing the former, CountryRisk.io looks at the government’s revenues, expenses and the underlying sources and uses of its income. The second part of the analysis—financing of the deficit—produces a fuller picture of the government’s fiscal flexibility.

CountryRisk.io assesses the quality of the government’s revenue base by looking at its size and various components—tax and non-tax—and judging each source’s sustainability. A captive tax base guards against external shocks, such as natural disasters, declines in tourism and changes in trade or foreign aid. In contrast, reliance on non-tax revenues increases revenue volatility and ultimately reduces fiscal flexibility.

Revenue trends are informative. To fund government spending without resorting to inflationary financing, the tax system’s ability to raise revenue is vital. This implies a tax system that generates revenue increases and grows in line with nominal income, without frequent changes in tax rates or the introduction of new taxes. A robust revenue and tax system enables the construction of fiscal buffers and enhances flexibility. CountryRisk.io also reviews the government’s willingness to increase revenue, as well as its dependence on privatisation and other one-off revenue sources that may not be sustainable for the funding of future (recurring) expenditures.

A government’s current and capital expenditures are central to assessing the quality and efficiency of its spending. Current expenditures consist of government wages and salaries, rents, transfer & interest payments and subsidies. These tend to account for a large share of the government’s total spending when the public sector is the primary employer and provider of goods and services, which is more common in emerging market economies. Sizeable current spending reduces fiscal room to manoeuvre and renders the government vulnerable to shocks, since it cannot respond effectively when access to market financing becomes constrained. CountryRisk.io assesses the government’s ability and willingness to rationalise this spending.

Superficially, capital spending consists of investment in infrastructure and other growth-enhancing programs. But this is a simplistic view because, although long-term growth should be the underlying goal, governments often pursue investment projects to achieve short-term macroeconomic effects, such as generating employment, or for political reasons. This kind of circumstance will dilute the long-term effects of such investment. The trends in the headline expenditure are as telling as the shift in shares between current and capital expenditures over time.

Against this background, the budget should be comprehensive, realistic, fully financed and forward-looking. Off-budget items reduce the budgetary policy’s effectiveness, as do unrealistic and inconsistent macroeconomic assumptions. They also lead to frequent budget revisions during the fiscal year, which reduces its reliability and credibility. A fully financed budget reflects realistic revenue projections and funding provisions over the declared fiscal period.

Government balances should reflect sound fiscal management and the resolve needed to maintain solid fiscal positions. When analysing fiscal deficits, it is critical to look at their underlying causes to determine whether they are temporary or recurring. With recurring deficits, it may be useful to consider the independence of fiscal managers and their ability to ignore pressure from all levels of government—local, regional, provincial and national.

A fiscal consolidation framework is also important to the anchoring of financial indicators and growth targets. While governments are likely to deviate from some goals during economic downturns or as a result of shocks, the analyst must consider the size of the shortfall as well as the speed and determination of the authorities in put its fiscal house in order again. A significant increase in deficits unaccompanied by a framework for adjustment may well drag the financial situation into an unsustainable decline.

Finally, CountryRisk.io considers a sovereign’s relationships with international organisations in three areas of policymaking. Countries that are members of multilateral institutions—whether supranational or a monetary union—and receive financing support in response to a fiscal or balance of payments crisis must adhere to the prescribed adjustment frameworks. This can be painful, but it is essential to correct the unsustainable imbalances that have developed. The government’s commitment to these conditions, if credible, helps to mitigate risk, since policy measures become more predictable and effective.

| Indicators | Adjustment Factors |

|---|---|

| Fiscal balance | Quality of revenue base |

| Revenue collection efficiency | Flexibility to raise revenues |

| Trends in government revenue versus nominal GDP growth | Expenditure performance and quality |

| Quality of fiscal management | Government’s willingness to cut spending |

| Adherence to demanding external programs |

Public debt sustainability

The sustainability of public debt becomes a serious concern when a government attempts to service its debt without significant fiscal adjustments. The analysis of public debt sustainability is multifaceted and its factors dynamic. The first step is a thorough assessment of a country’s current debt situation, looking at factors such as headline and other liabilities that are or may become reliant on the government, currency and maturity structures, the composition of its borrowing rates and the holders of its debt.

To assess the current level of debt, it is not enough to consider the government’s own debt alone. The analysis must also incorporate liabilities arising from state-owned enterprises (SOEs), public-private partnerships (PPPs) and pension and healthcare programs. As an example, although SOEs are quasi-governmental enterprises, they are expected to generate sufficient revenue to service their own debts. In fact, in many countries, the liability for some or all SOE debt shifted to the government. As a result, these quasi-governmental enterprises are unable to borrow on foreign capital markets, leaving the government to do so on their behalf. These funds are sometimes called “on-lend” money, which the government borrows and “lends” onward to an SOE. In the end, this sum only adds to the sovereign’s headline debt. Absent any improvement in the SOE’s financial position, the obligation rests entirely on the government.

In general, the higher the level of public debt, the more likely it is to become unsustainable. All things being equal, higher debt requires a higher primary surplus to stabilise it. That said, higher debt ratios are usually related to higher interest rates and imply servicing by an even higher primary balance. Research in the wake of the recent sovereign debt crises in Europe suggests that debt levels above 60% of GDP should trigger a thorough debt sustainability analysis for a sovereign.

When analysing debt sustainability, it is important to have realistic baseline assumptions concerning the country’s growth rate, interest rate and primary balance over a five- to ten-year period. For a comprehensive analysis, incorporating country-specific issues such as its vulnerability to shocks—whether economic, political or natural in origin—is also critical. Not only are these factors relevant to assessing baseline debt sustainability, but they also deepen the risk analysis of potential stress scenarios. Higher interest rates—for example, changes in market sentiment or lower growth assumptions due to unfavourable debt dynamics—require upward adjustments in the primary balance to stabilise the debt ratio. All of this could alter the initial assessment of debt sustainability. CountryRisk.io includes granular debt sustainability calculations alongside simpler calculations for countries where limited data prevents a more detailed evaluation.

The other areas of vulnerability we consider are the size of the government’s net assets, whether its debts are concessional or raised from the markets, whether market debt is borrowed on domestic or foreign capital markets and whether the country can easily access funds from other sources. These observations are relevant to assessing potential refinancing concerns if debt dynamics were to deteriorate.

As a further element in its analysis, CountryRisk.io assesses the government’s debt payment culture. This assessment considers the degree to which policymakers are willing to prioritise servicing debt obligations and risking default. It examines the sovereign’s history of: (a) arrears on official bilateral debt; (b) any public discourse that questions the legitimacy of debt contracted by a previous administration (odious debt); and (c) policy changes since the most recent default on commercial debt.

| Indicators | Adjustment Factors |

|---|---|

| Size of total government debt to GDP | Government assets |

| Size of debt servicing to tax revenues | Government access to funding |

| Public external debt service to exports | Contingent liabilities |

| Public debt profile | Government’s debt payment culture |

| Uncertainty of baseline projections |

Balance of payment flexibility and external debt sustainability

CountryRisk.io’s analysis of a country’s external position considers its external liquidity and the viability of its external debt.

Conventional wisdom states that persistently large current account deficits—over about 5% of GDP—are unsustainable. However, history reveals mixed findings, as a number of countries have been able to run large current account deficits for years while avoiding external crises. Others, though, have suffered considerably.

CountryRisk.io applies a framework that considers the fundamentals underlying the current account as well as indicators from the capital account. The framework also examines potential areas of vulnerability in the country’s economic structure, macroeconomic policy and political economy that could heighten external account instability.

In this version of the model, we begin by accounting for a country’s currency status and the frequency with which its currency is traded in the global foreign exchange markets as indicators. The previous version of the model ignored these attributes because other characteristics of strength—such as the quality of institutions and legal framework, the flexibility of the exchange rate and the depth and breadth of the capital markets—ameliorate any vulnerability it may have had in its external debt profile. However, by recognising the weight of its currency in global markets, we can exclude other external indicators—primarily those that assess external liquidity, such as import coverage—from the assessment. This is because these countries tend to issue debt in their currencies, which means that, due to the strength of their institutions and other mitigating qualities, such countries are unlikely to renege on their obligations.

CountryRisk.io uses several metrics to measure external liquidity, including import coverage, external financing requirements as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) and the IMF’s reserve adequacy ratio (RAR). Import coverage, expressed in numbers of months, depicts the adequacy of foreign exchange reserves to pay for imports. While this is a useful measure of external liquidity, it is narrowly defined and more appropriate for low-income countries, as defined by the IMF.

We regard the external financing requirement and RAR as more robust indicators of external liquidity, with the former taking into account sources of external vulnerability such as the size of a country’s current account balance, short-term external debt and principal payments. Clearly, without sufficient useable foreign exchange reserves, a country running current account deficits and facing large payments due over the next twelve months is likely to run into liquidity issues.

The reserve adequacy ratio considers these factors as well, but extends its analysis by including the maturity, depth and underlying liquidity of a country’s market as well as its economic flexibility.

Liquidity issues become even less favourable when a country’s export base is narrow or highly dependent on commodity imports. However, such a country can reduce that risk through increased diversity in its composition of trade and trading partners.

The make-up of a country’s external liabilities can be another source of vulnerability. Again, here, CountryRisk.io distinguishes between debt, equity and their respective instruments. In general, foreign investors bear part of the equity financing burden, which allows asset price adjustments to absorb at least some negative shock. However, assuming that it does not default, debt financed in a foreign currency places most of the burden on the borrower through the depreciation of the domestic currency.

The structure of equity and debt liabilities is equally important. When compared to foreign direct investments (FDI), portfolio investments are often regarded as potentially more volatile. In assessing debt, we look at its maturity and interest structures as well as its currency composition. Short-term maturities increase rollover risk, as does a bunching of maturities. A high amount of foreign-currency-denominated debt as a proportion of total debt (public and private) and/or a high prevalence of floating interest rates can render the country vulnerable to external shocks.

A relatively open capital account can be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it exposes the country to volatile capital flows. However, it also allows the country to adopt policies designed to help it adjust to adverse external shocks. Meanwhile, a relatively closed capital account shields the country from unexpected fluctuations in foreign capital flows. That said, it may also cause considerable imbalances in the economy that could lead to a crisis in a fixed exchange rate regime.

The flexibility of a country's exchange rate is closely linked to its exchange rate policy. Time and again, history has shown that countries pursuing a fixed exchange rate regime are prone to speculative attacks precipitated by external shocks. Against this backdrop, the real effective exchange rate becomes a useful barometer of sustainability. Meanwhile, a real appreciation of the exchange rate is not a cause for concern if fundamentals, such as productivity improvements or more favourable terms of trade, support the increase.

Nonetheless, a persistent real appreciation of the exchange rate in a fixed or managed exchange rate regime may indicate conflicting monetary and exchange rate policies that could eventually result in overvaluation. Capital controls, combined with high domestic interest rates, typically support such overvaluation. Dynamics can worsen quickly, with the sustainability of the current account soon becoming vulnerable to slowing economic activity brought on by higher interest rates. At the same time, the appreciating currency leads to a decline in exports. The subsequent widening of the current account deficit and decline in foreign exchange reserves reinforce the expectation of a devaluation, further weakening the country’s ability to defend its external imbalances.

Historically, large capital inflows into many emerging market economies have caused an appreciation in their real exchange rates. For some countries, improvements in their fundamentals provided an anchor. For others, large capital inflows have excessive short-term effects, which ultimately lead to increased exchange rate volatility and current account imbalances.

The indicators and adjustment factors in the “Balance of payment flexibility” risk category are listed below.

| Indicators | Adjustment Factors |

|---|---|

| Current account balance | Share of net fuel imports to total imports |

| Reserve currency status | Fluctuations in the terms of trade |

| Actively traded currency | Remittances and other non-debt creating sources of reserves |

| Export performance | Liberalisation of the capital account |

| Diversification of the export base and markets | Quality of foreign investments |

| Real effective exchange rate valuation | |

| Net international investment position |

The indicators and adjustment factors in the “External debt sustainability” risk category are listed below.

| Indicators | Adjustment Factors |

|---|---|

| Total net external debt to GDP | History of default |

| Net external debt to exports | Risk of a sudden stop |

| Size of short-term external debt to FX reserves | |

| Interest payments on external debt to exports | |

| External debt profile | |

| Import coverage | |

| External financing requirements | |

| Reserve adequacy ratio |

Environment

Within the context of sovereign credit risk assessments, CountryRisk.io starts with the premise that environmental factors are those that affect the sovereign’s physical assets and other production inputs, which it could use (implicitly) as collateral for debt obligations. We then mapped the indicators we found to be material into two sections: (1) climate change and renewable energy, and (2) biodiversity.

Climate change has far-reaching consequences on a country’s economic activity through various channels. Physical risks stemming from rising average temperatures or extreme weather phenomena, such as storms, hurricanes and earthquakes, could impair countries’ medium-term ratings whether or not they are rich in natural resources. For instance, the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines in 1991 not only caused significant human and animal casualties, but also damaged agricultural land, crops and infrastructure far beyond the volcano’s immediate vicinity. The ensuing destruction and continued ash fall in the following days disrupted otherwise flourishing local economies. Household incomes declined markedly as economic activity ground to a halt, while key development activities and priorities changed. The government, which at the time had very limited fiscal space, stepped in to help finance the region’s recovery, relief and prevention of further damage.

In general, countries prone to natural disasters could see downward pressure on the sovereign’s credit ratings from several sources, including lower output, increased public debt and deficit or a marked contraction in exports.

Another way in which resource-rich economies are vulnerable to climate change is the degradation of a natural environment from which they derive significant revenue and wealth. Although this may only impact their sovereign ratings over the medium-term, we must still consider mitigating factors that could maintain the sovereign’s current rating, such as policies designed to encourage economic diversity and reduce its reliance on a single revenue source.

Other environmental issues worth considering include the quality of the environment and its impact on public health, such as healthcare costs resulting from air pollution.

CountryRisk.io regards renewable energy as a mitigating factor against the growing impact of global warming. As many studies show, the energy sector is responsible for around two-thirds of greenhouse gas emissions, making carbon-free energy a safe, affordable and reliable way for a country to reduce its overall carbon footprint.

However, we must also bear in mind that the transition risks that arise as a country reduces its carbon footprint could also undermine its medium- to long-term ratings. Depending on a country’s energy strategy and the extent to which it is dependent on fossil fuels, the transition towards a low-carbon economy could be disruptive and costly. The nature of a country's decarbonisation strategy, which includes the speed of transformation, policy coordination and other related technical issues, may expose the country to economic losses by way of asset write-downs or devaluations.

| Indicators | Adjustment Factors |

|---|---|

| ND-Gain country index | |

| Level of greenhouse gas emissions | |

| Greenhouse gas emissions growth rate | |

| Decoupling of economic growth from carbon emissions | |

| Physical risks due to climate change | |

| Transition risks due to climate change | |

| Government policies to fight climate change | |

| Policies for climate risk management | |

| Energy intensity of primary energy | |

| Renewable energy availability | |

| Access to sustainable and modern energy |

CountryRisk.io considers biodiversity to be highly dependent on climate change. Combined with the effects of human activity, such as pollution, over-extraction, land degradation and deforestation, climate change is markedly changing our ecosystems. Many plant and animal species are rapidly dying out, which will have extensive effects on air quality, fresh water availability, soil quality and crop pollination. Therefore, among the many relevant areas for consideration, we regard government policies designed to promote a circular economy as being very important. Although the assessment of such policies is, essentially, a judgment call on behalf of the analyst, we believe that such an evaluation is indicative of a government’s commitment to reducing or eliminating waste and pollution and, ultimately, its implicit resolve to mitigate climate change.

| Indicators | Adjustment Factors |

|---|---|

| EPI Biodiversity & Habitat Index | |

| Depletion of natural resources | |

| Forest coverage | |

| Government policies to fight biodiversity loss | |

| Government policies to promote circular economy |

Social

Social considerations may not seem particularly relevant to sovereign ratings. However, basic services to a country’s citizens are integral to ensuring social cohesion which, in turn, tends to reflect the quality of its institutions and strength of its policymaking. Indeed, as set out in the standard country risk framework, inadequate services, will, over time, undermine fiscal finances, which may put pressure on its ratings.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed vulnerability in otherwise highly-rated countries’ healthcare systems in terms of their quality, resilience and overall capacity to deal with a crisis. Indicators in this area include the number and availability of intensive care beds, ventilators and personal protective equipment relative to population size. Examining such indicators could yield a partial explanation for why and how certain advanced economies, such as the United Kingdom and the United States, have seen more virus-related deaths per capita relative to other such economies. Meanwhile, indicators of overall population health include measures such as the prevalence of heart conditions.

Within the ESG sovereign risk model, the social risk factor is split into three subgroups: health, food security & poverty and labour market & social safety nets.

Health, food insecurity and poverty

A healthy population is vital for economic development and progress. Ultimately, the current health of the population is reflected in its present life expectancy, while its likely future health is indicated by life expectancy trends. Rising healthcare costs can put a substantial strain on public finances and depress productivity. Hence, effective public healthcare systems are crucial not only for improving the overall health of the population, but also for healthy public finances. Relevant indicators for calculating the health risk score include the immunisation rate, access to clean water & sanitation and the impact of air pollution on health.

CountryRisk.io recognises food insecurity and poverty as key risk drivers for the social pillar, and we assess them in several dimensions. For instance, each could precipitate civil unrest if widespread economic hardship were protracted, thereby affecting growth as investments dry up. For countries whose initial debt sustainability conditions were already questionable, social instability may push it even closer to the brink. Food insecurity could also worsen if the country’s currency experiences a sharp depreciation, making food imports more costly.

| Indicators | Adjustment Factors |

|---|---|

| Strength of public health | |

| Quality of the healthcare system | |

| Prevalence of undernourishment | |

| Food insecurity and government policies to fight hunger | |

| Prevalence of poverty | |

| Risk of humanitarian crises and disasters |

Labour market and social inclusion

The labour market plays a critical role in sovereign risk in several ways, although the two principal factors are growth and public finances. In general, a country with low unemployment or full capacity suggests an efficient labour market which, in turn, indicates stable growth, a broader tax base and a lower fiscal burden for unemployment subsidies. Where unemployment benefits become necessary, we examine the extent of government support on the one hand, and whether such support is appropriately targeted to poor and vulnerable households on the other.

An economy can only thrive if every citizen can take part in society and the economic process on an equal footing. Firstly, inclusion refers to citizens’ ability to access not only education and healthcare, but also the banking system, formal labour market and democratic processes, such as elections. Secondly, equality means creating a level playing field for everyone and removing any form of unjust discrimination.

| Indicators | Adjustment Factors |

|---|---|

| Unemployment rate | Structural unemployment |

| Youth unemployment rate | |

| Labour force participation rate | |

| Quality of labour market policies | |

| Income equality | |

| Social safety nets and work-life balance | |

| Gender equality in the labour market |

Transfer and convertibility risk

The T&C risk score assesses the incentives and costs versus benefits of the government introducing capital or exchange controls. While such controls offer some advantages to the government by preserving foreign exchange reserves and limiting capital outflows in times of stress, capital controls typically harm the private sector. Widespread corporate sector defaults on external or foreign-currency debt, along with loss of access to foreign sources of financing and international suppliers & customers, constitute a severe burden on the private sector and, by extension, the sovereign, such as through declining tax revenues, higher social expenditures and increasing contingent liabilities. In general, countries that have strong institutions and are well integrated into the world economy, whether through trade or financial linkages, are less likely to introduce capital controls.

The indicators in the “Transfer & convertibility risk” category are listed below.

| Indicators |

|---|

| History of imposing exchange or capital controls |

| Member of a monetary union |

| Integration with global economy |

| Institutional quality and rule of law |

| Private sector leverage in foreign currency |

| Reserve currency and frequently traded currencies |

| Financial offshore center |