Why addressing forest degradation is at the heart of combating climate change and biodiversity loss

Bernhard Obenhuber

Jun 29, 2021

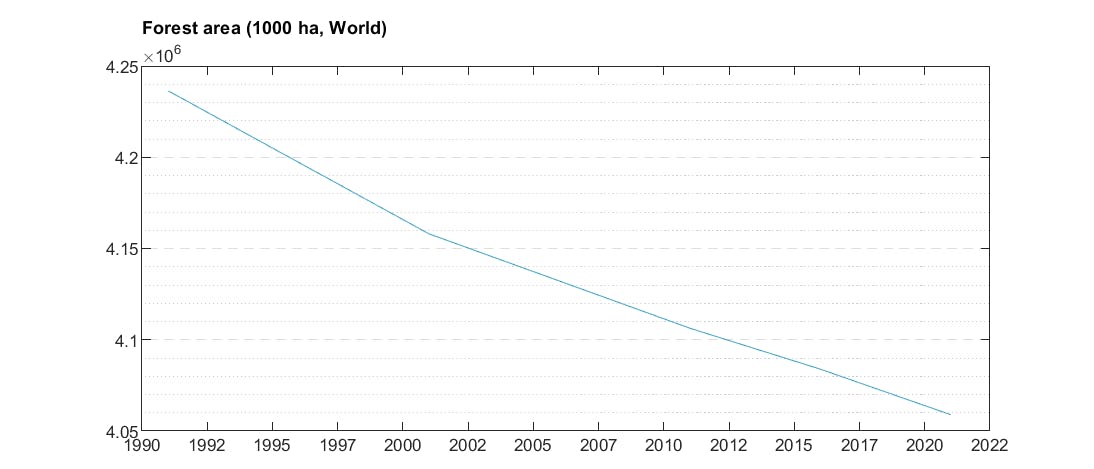

Driven by human activities, the dual crises of climate change and biodiversity loss pose a threat to nature, livelihoods, well-being, and human lives. To mitigate climate change and protect species, preservation of forests must be at the top of the global agenda, given that the globe’s forests absorb one-third of annual CO2 released from fossil fuels and are home to 80% of the world’s terrestrial biodiversity. Despite this, one hectare of tropical forests is destroyed or drastically degraded every second. Based on the latest data from the FAO, we have lost more than 170 million hectares of forests between 1990 and 2020 as shown in the chart below.

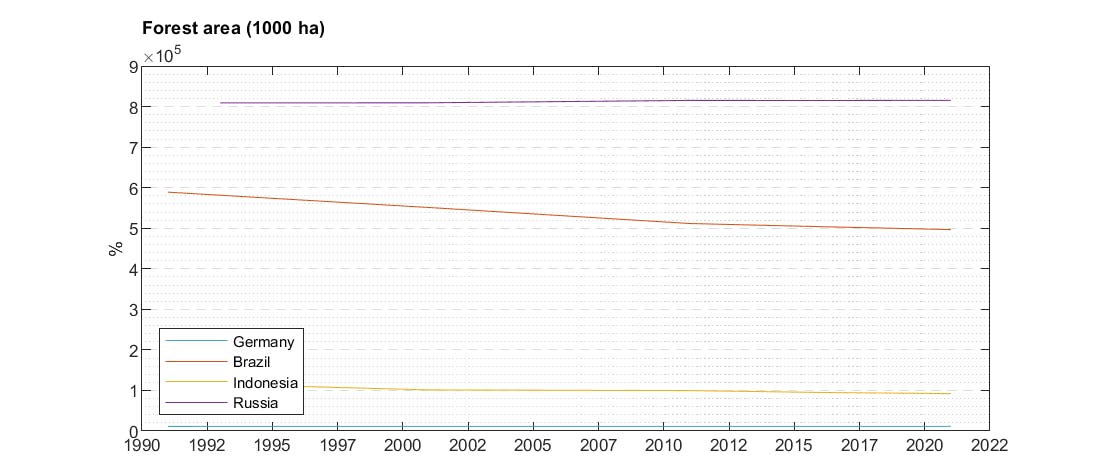

Over this period, Russia – home to the largest forest area on the planet – has not seen deforestation, but rather the contrary, as forest area increased by 6 million hectares. In contrast, Brazil is a real problem given its large size and hence importance on a global scale but has experience substantial deforestation. Indonesia has also seen substantial deforestation in recent decades.

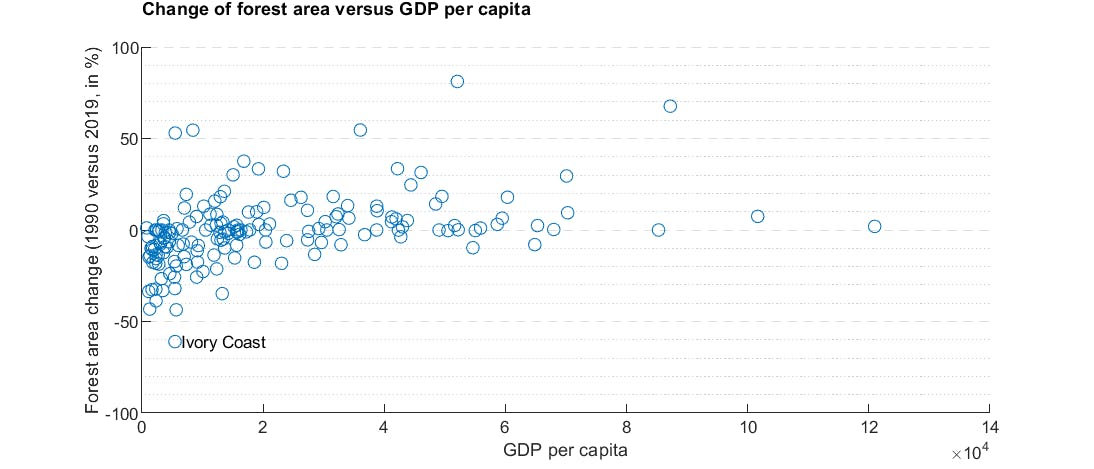

Overall, when we look at all the countries and the respective change of forest area between 1990 and 2018 as shown in the chart above, we can see that clearly more countries lost forest area than countries that increased forests. The chart also shows that low-income countries have seen especially large deforestation. For example, Ivory Coast lost nearly 60% of forests during the three decades, and consumer’s chocolate consumption might have had something to do with it.

Deforestation - Degradation

The role deforestation has played in disrupting the carbon cycle and ecosystems has been widely acknowledged, however the impact caused by degradation – where parts of the forest are damaged but not destroyed – has been vastly understated.

While not as obvious a scourge as deforestation, forest degradation is in reality the more pressing issue. A new reportrevealed that forest degradation in the Brazilian Amazon accounted for three times more carbon loss than deforestation. Meanwhile in Europe, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) reported that an estimated 3.7 million hectares of the continent’s forests are damaged by livestock, insects, diseases, forest fires and other human-linked activities.

Ultimately, forest degradation is at the centre of a vicious circle. It’s the largest process creating carbon loss, which is causing extreme climate events such as droughts, which in turn increase tree mortality and damage to forests.

Combating biodiversity loss and climate change together

Biodiversity loss and climate change driven by forest degradation from human activities sheds light on how these two crises mutually reinforce each other and will require a coordinated approach if they are both to be solved. This was the key finding of a recent report by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) which argued that addressing the synergies between mitigating biodiversity loss and climate change, while considering their social impacts, offers the best opportunity to meet global development goals.

A closer look at how a joined-up approach to tackling forest degradation and deforestation shows how benefits can be maximised. For example, growing trees on grasslands can destroy the plant and animal life of a rich ecosystem, even if carbon is sucked up by the new trees. Similarly, while solar farms generate clean energy, they can eliminate wildlife habitats. Ultimately, climate interventions, such as planting trees in new areas to combat forest degradation can hurt biodiversity. Such trade-offs highlight the problems associated with failing to develop a harmonised approach and addressing biodiversity loss and climate change in silos.

“Just like the net zero climate transition, the global economy will need to dramatically change course to address the nature crisis. If financial institutions fail to consider nature risks in parallel with climate risks, their outlook on the market value of different sectors will be distorted. For example, research suggests that current market expectations for industries like bioenergy could be overstated by a factor of 30 if we only account for climate risks," says Charlie Dixon, Portfolio Manager at Finance for Biodiversity, whose recent report The Climate-Nature Nexus explores this further.

Incorporating degradation into sovereign risk analysis

We wrote earlier on the growing interest in natural capital accounting as an effective system to measure dependence on natural resources such as forests and wetlands, as demonstrated by the recent adoption of the System of Environmental-Economic Accounting – Ecosystem Accounting (SEEA EA) by the UN Statistical Commission. But a shift to natural capital accounting is still in its infancy and, while stock of natural capital as a measurement of wealth is being assessed by factors such as the deforestation level, we still need to see forest degradation level introduced as a metric. This could come sooner rather than later since geospatial data with the use of satellite imagery can now show the density of plant growth. With further high frequency signal advances, this data could provide consistent tracking of forests.

Preservation of a country’s forests is an indicator of sovereign risk in both environmental and economic terms since forest cover is increasingly seen as an asset on a nation’s balance sheet. Consequently, forest degradation must not be overlooked in sovereign risk analysis. However, implementing policies to strengthen natural capital and biodiversity by reversing forest degradation will require time and careful consideration. An innovative approach will be needed since halting degradation is much more complex than stopping clearcutting and illegal logging.

Although data quality for tracking biodiversity loss is improving, a data gap still exists. Meanwhile, there is an even larger data gap for monitoring what actions governments around the world are taking to counter environmental degradation. However, if this gap can be closed, expect pressure to mount on countries to improve their efforts in preserving biodiversity. For instance, dozens of institutional investors have demanded Brazil halt deforestation in the Cerrado, while the $19 trillion EU-Mercosur trade pact is facing growing opposition from the EU parliament over Brazil’s deforestation of the Amazon.

Country-level sovereign sustainability performance is a fast-evolving space and, while the sovereign risk community is increasingly factoring in climate change into its analysis, it must now begin acknowledging the importance of the entire ecosystem. We at CountryRisk.io firmly believe that metrics such as carbon intensity, biodiversity loss vulnerability and forest degradation level should figure prominently in sovereign risk ratings. We have therefore embedded several aspects of the quality of spending and assessments of the usage of natural resources into our platform (CountryRisk.io Rating Methodology).