Sovereign rating review: first quarter 2021

During the first quarter of 2021, the Big Three rating agencies downgraded 11 sovereign ratings and upgraded four.

Dr. Moritz Kraemer

Apr 12, 2021

Summary

— During the first quarter of 2021, the Big Three rating agencies — Fitch Group (Fitch), Moody’s and S&P Global Ratings (S&P) — downgraded 11 sovereign ratings and upgraded four. After a flurry of activity in March and April 2020, the number of rating changes began to decline and have now returned to normal levels with no sign of a second wave.

— Once again, emerging and developing countries in sub-Saharan Africa and the Western Hemisphere have borne the brunt of the downgrades. S&P was both the most active and most negative agency during Q1. Meanwhile, Moody’s upgrades and downgrades were balanced.

— Although CountryRisk.io also made fewer changes to its sovereign risk scores in Q1 compared with previous quarters in 2020, they continue to signal more changes to creditworthiness than the ratings of the Big Three agencies. During Q1, our sovereign risk scores — which depend exclusively on quantitative analysis and are continuously updated — were lowered in 19 cases and increased in nine.

Introducing a quarterly review of sovereign rating actions

CountryRisk.io’s easy-to-use platform generates sovereign risk scores via an algorithm. Beyond selecting the input data, we apply no further direct discretion. While we convert our sovereign risk scores into the standard rating scale symbols for comparability, our scores are not “ratings” in the regulatory sense. CountryRisk.io does not hold a rating license and has no intention of applying for one. Nevertheless, we designed our platform’s sovereign risk scores to measure the same credit risks as the equivalent regulatory-approved ratings from the Big Three agencies.

Since Fitch, Moody’s and S&P combine quantitative assessments with qualitative judgements, it is helpful to periodically compare the performance of our purely quantitative, algorithmic approach to sovereign risk scores with the Big Three’s more judgement-based ratings. This is the first instalment in what we plan to be a quarterly review of CountryRisk.io’s sovereign ratings performance.

If you have any feedback or suggestions for future editions, we would love to hear from you at [email protected].

Few rating actions in early 2021

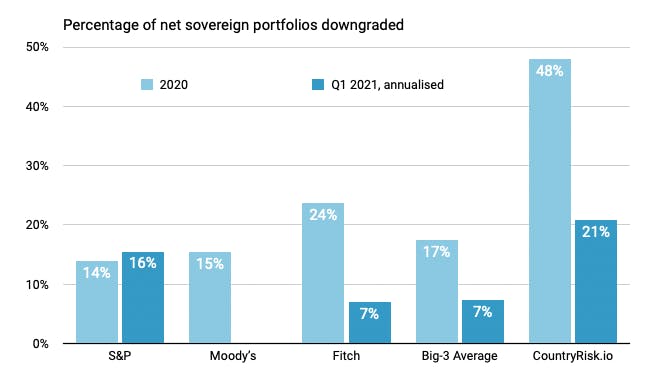

The first conclusion we can draw from the aggregate data is that rating activity slowed in Q1 compared to 2020 (see Chart 1). In fact, as we have shown elsewhere, the frequency of rating actions began to significantly decline as early as the second quarter of 2020, a trend that continued into 2021. January was the first month in which the Big Three did not make a single sovereign rating change since November 1993!

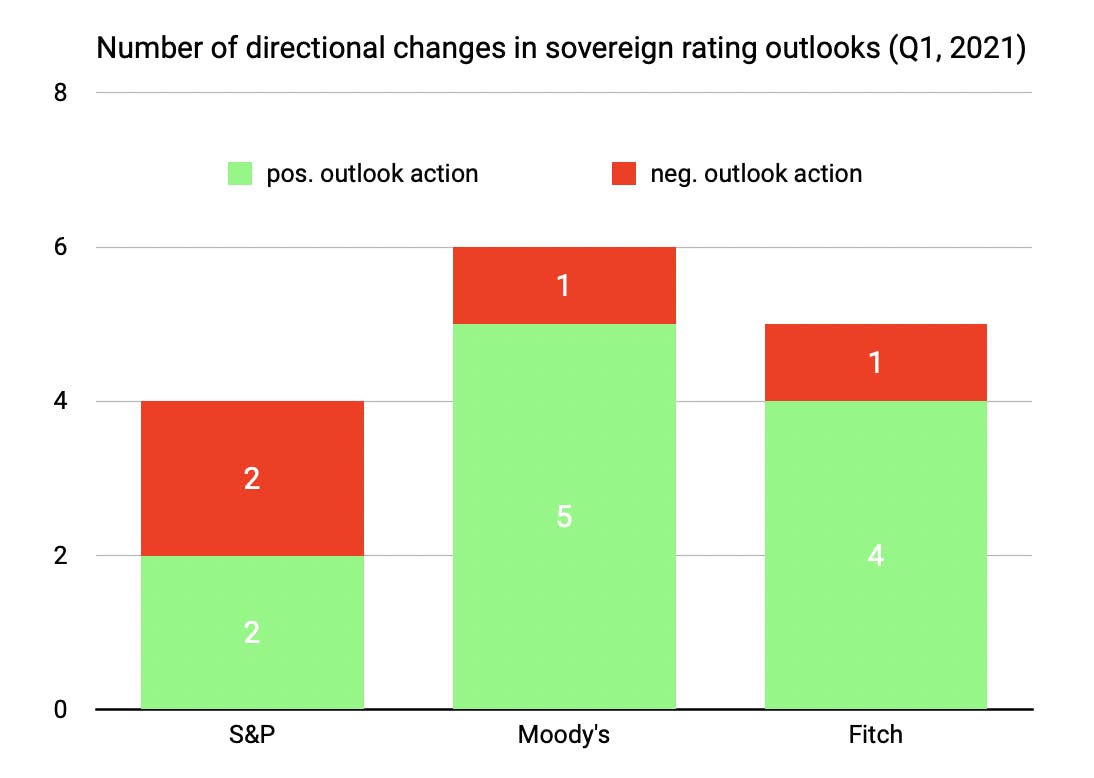

Overall, the balance of sovereign rating actions remained on the downside during Q1. Moody’s, which implemented an equal number of rating upgrades and downgrades, was the notable exception (see Table 1 for a comprehensive list). Fitch, which was the most active agency in the early days of the pandemic, made the fewest rating changes during Q1. Meanwhile, S&P, which was slower to change ratings in 2020, may have some catching up to do (at least outside sub-Saharan Africa, where S&P had been the most aggressive of the Big Three).

CountryRisk.io’s algorithmic model has also resulted in an easing of the downgrade trend. However, as it was last year, our downgrade trend remains more pervasive than any of the Big Three’s. In Q1, CountryRisk.io’s model downgraded (net of upgrades) 21% of our (larger) rated portfolios on an annualised basis, three times more than the Big Three average of 7%.

The worst may soon be over, say the agencies

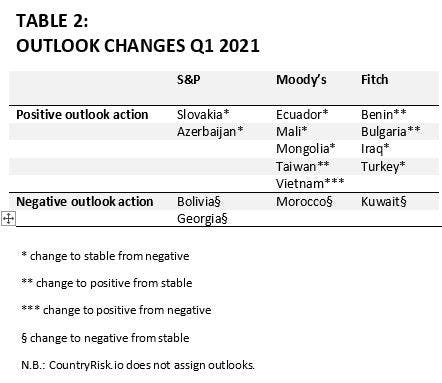

Unlike CountryRisk.io, the Big Three agencies use rating outlooks to indicate whether the next change is more likely to be an upgrade (in the case of positive outlooks) or a downgrade (negative outlooks). Both Fitch and Moody’s have displayed a strong tendency to improve outlooks during Q1 (see Chart 2 and Table 2 for details). This may indicate that, as far as those agencies are concerned, the worst may soon be behind us in terms of net downgrades. S&P, on the other hand, painted a balanced picture, with an equal number of positive and negative outlook revisions. This observation is also in line with the hypothesis that S&P has acted less quickly during the crisis (at least compared to Fitch) and may not be done working down its to-do list.

The split between rating actions for rich and poor countries persists.

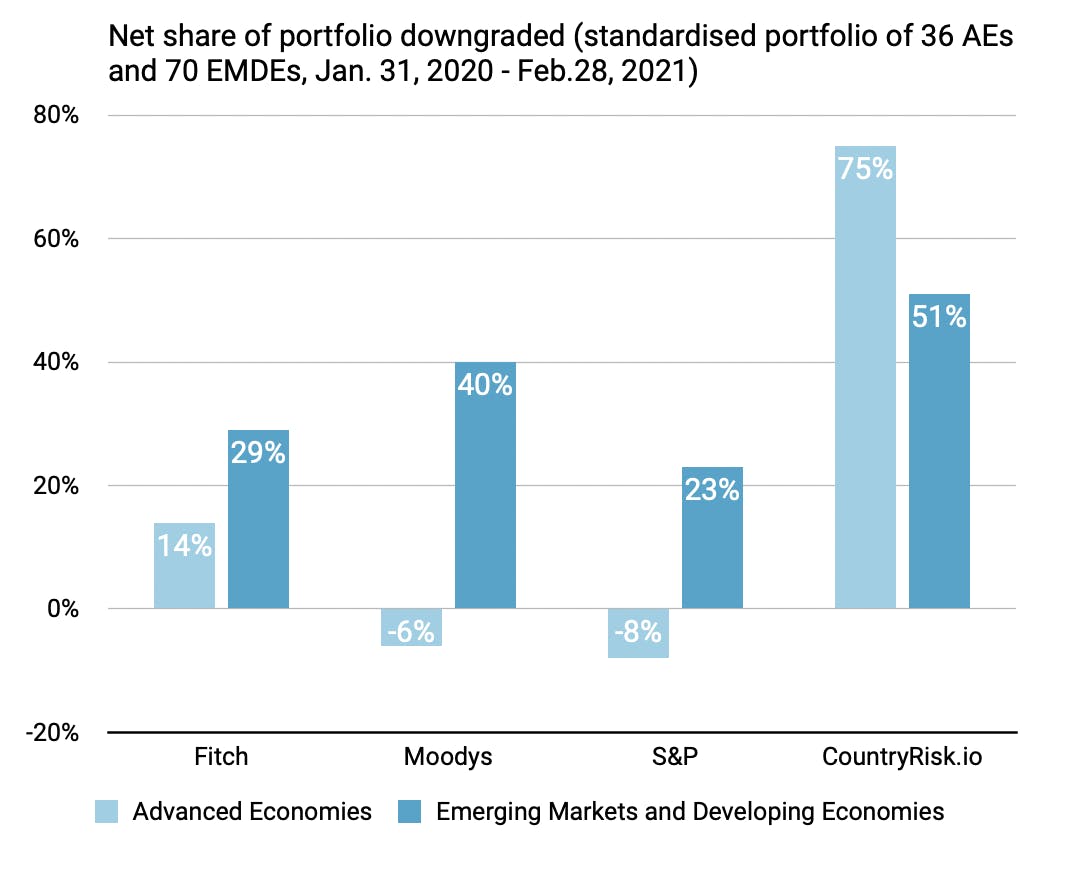

During the pandemic, emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) bore the brunt of downgrades. Chart 3, reprinted from our assessment of sovereign rating performance throughout the COVID-19 crisis, shows how, on a standardised portfolio (106 sovereigns rated by the Big Three), advanced economies got off virtually scot-free, despite their economies and public finances being more severely affected than those of EMDEs. Accordingly, and in contrast to the Big Three, CountryRisk.io’s parametric assessment resulted in a more severe downward trend for rich countries than for poor.

More downgrade pressure for highly rated sovereigns also makes sense considering the historic observation that the probability of default changes only incrementally between ratings at the top end of the scale. In contrast, lowering an already low rating by the same number of notches indicates a bigger increase in the likelihood of default. Therefore, a constant increase in default probability should lead to bigger downgrades at the top of the ratings ladder, where most rich countries reside. This is what the CountryRisk.io’s sovereign risk scores have shown, but not the rating actions of the Big Three.

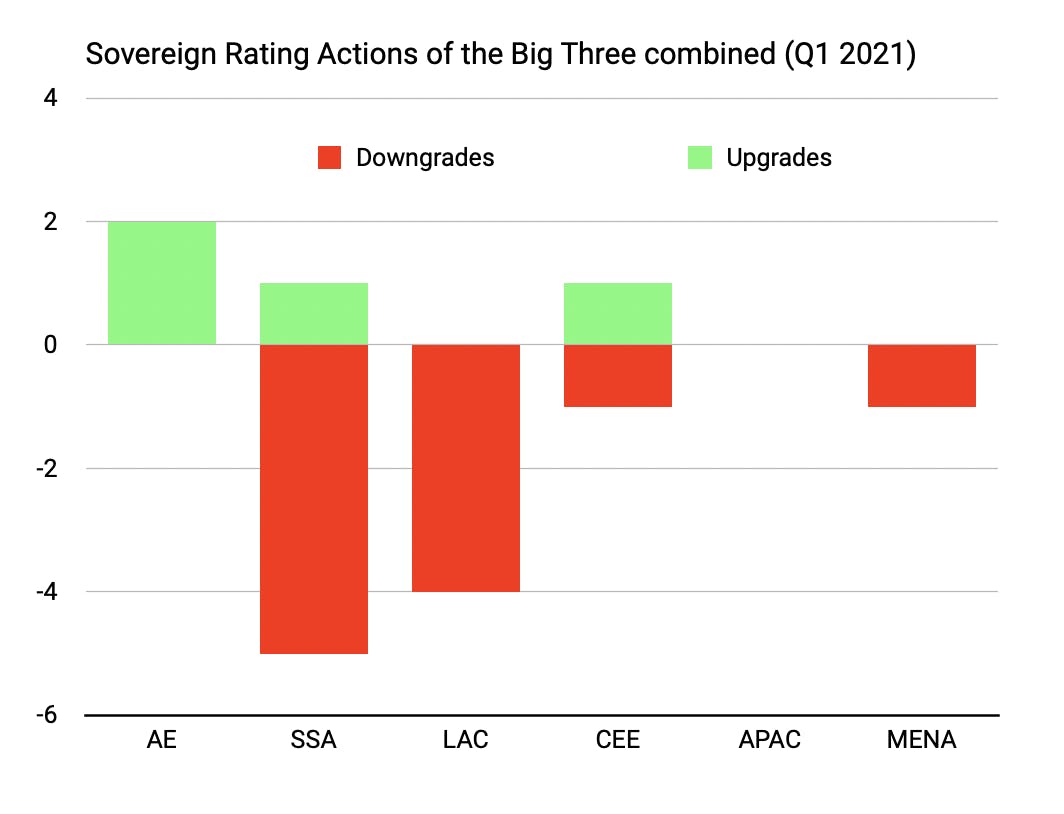

Since early 2020, sovereigns in the Caribbean & Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa have been hit hardest by rating downgrades. That is still the case. Chart 4, which shows the absolute combined number of the Big Three’s upgrades and downgrades (see Table 1 for full details) during Q1, reveals that these two regions remain the most affected by downgrades, accounting for 80% of the total. Again, advanced economies received more lenient treatment. They even enjoyed net upgrades. There were no rating actions in the Asia-Pacific (APAC) region, and little to report in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) or Emerging Europe (CEE).

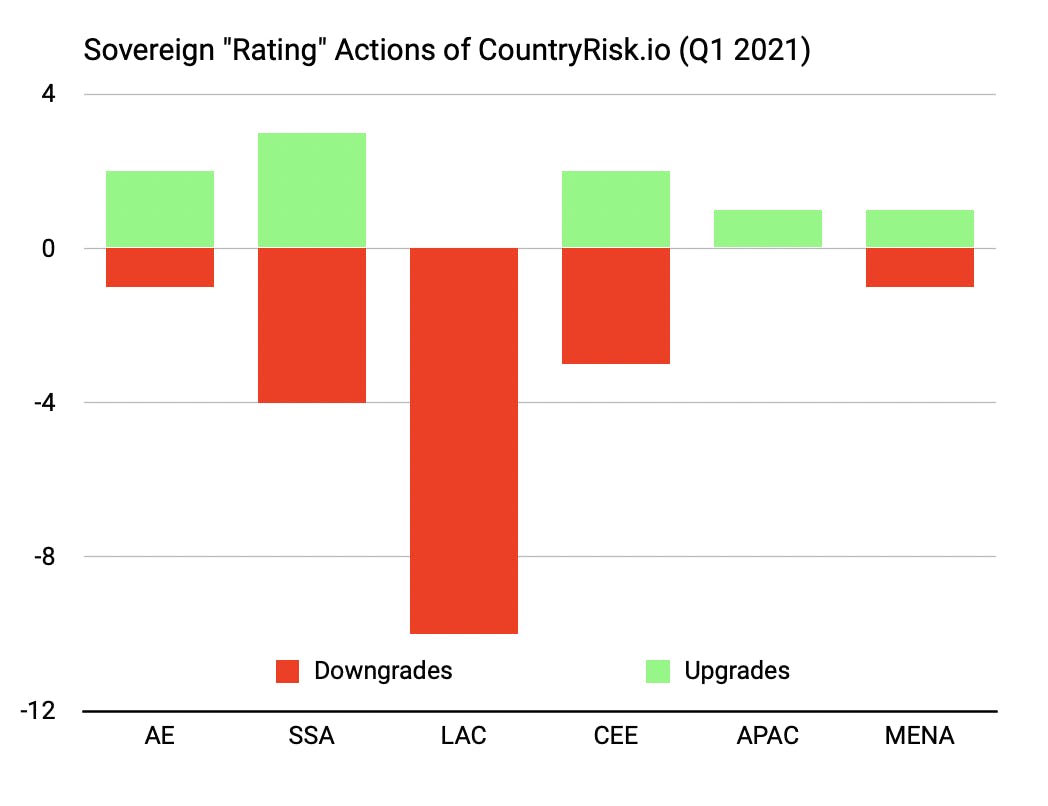

Like the Big Three’s ratings, CountryRisk.io’s algorithmic scores reflect a rather dim view of Caribbean and Latin American sovereign creditworthiness (see Chart 5). Unlike the Big Three, though, CountryRisk.io presents a less gloomy view of African sovereigns. CountryRisk.io also downgraded an advanced economy — the Netherlands — partly offsetting the upgrades of Portugal and South Korea in that country group.

A closer look at individual rating actions

Among the agencies’ rating actions during Q1, some merit a closer look.

One positive development was the first upgrade of a sovereign in sub-Saharan Africa since the pandemic began when Moody’s raised Benin’s rating to B+ in early March (the standard rating scale is used throughout for ease of reading). In early February, Benin also received a positive outlook from Fitch. We agree. During our webcast on 10 March, we pointed out that Benin (along with Cote d’Ivoire) is standing out positively in the region in terms of credit metrics. The rating and outlook improvements by Moody’s and Fitch followed the successful issuance of two heavily oversubscribed Eurobonds in January, including one with a record 30-year tenor. This sequence of events may raise questions around whether the agencies are, at least subconsciously, following market sentiment rather than unerringly leading from the front in assessing fundamentals.

Ethiopia, on the other hand, received two downgrades last quarter (from Fitch and S&P, while Moody’s put it under review for a downgrade) following Addis Ababa’s announcement that it will seek a debt restructuring under the G20 Common Framework. Any debt relief granted by official creditors is contingent on the comparable treatment of all creditor groups, which would trigger a restructuring of Ethiopia’s only outstanding Eurobond irrespective of its relatively small size. That would constitute a distressed debt exchange, which is tantamount to a default.

Another sovereign destined to default (again) in the coming months is Belize. Belize has many challenges, one of which is a lumpy debt structure: its 2034 ‘Superbond’ accounts for a quarter of all government debt. The slide in public finances in this tourism-dependent country will make it next to impossible, both financially and politically, for Belize to make its coupon payment due in May. S&P duly lowered Belize’s rating to ‘CC’, the antechamber of default — set to be Belize’s fifth since 2006. On March 31, Suriname defaulted (again) by missing $50 million of previously rescheduled external debt service.

Fitch improved its outlook on Bulgaria from stable to positive on 19 February. This development seems relatively unremarkable — after all, Moody’s upgraded Bulgaria last October, and the country has done comparatively well since. But it is precisely this argument that is interesting. Fitch changed its outlook on the basis that, while Bulgaria’s fundamentals were under pressure (understandable, in a global pandemic), its key indicators deteriorated less than previously feared. In other words, Fitch’s improved outlook on Bulgaria was the result of “it could have been worse” reasoning.

Similar logic underpinned Moody’s upgrade of Serbia on 12 March, when the agency argued that Serbia’s recession “compares well with regional and rating peers”. That statement is probably true. However, we are still in the midst of both a recession and a global pandemic. A crisis less severe than feared would be a perfectly valid reason to refrain from downgrading. But we are starting to see positive rating actions not based on innproving fundamentals, but on the back of fundamentals not being hit as hard as they could have been. Had Bulgaria or Serbia experienced equally bad economic crises in 2019 or earlier, they would have been prime candidates for downgrades. Now, however, their rating trajectories point north.

This raises an interesting question: are ratings becoming more relative? In other words: Will downward rating pressure mount for all if fundamental credit metrics deteriorate for all? Or will the judgmental component of the methodology be applied to treat sovereigns whose metrics exhibit (relatively) smaller deterioration as equivalent to an improvement, thus meriting positive action? It remains to be seen whether Q1’s improved outlook balance, while much of the world was still under lockdown, represents the anticipation of a brighter post-pandemic world or the beginning of a gradual shift toward more relative rating methodologies. If it turns out to be the latter, we should expect observed default rates to creep up at each rating level compared to historical observations. We will learn more over the coming months and revisit this question in future quarterly rating reviews.

Another interesting action was Fitch’s outlook change on Kuwait from stable to negative on 2 February. Until last year, Kuwait had the most stable sovereign rating among the wealthy Gulf sovereigns, having held an ‘AA’ rating from all agencies for decades. Then came two downgrades from Moody’s and S&P (double-notch from the former!) last year, with a downgrade from Fitch now all but certain to follow. Kuwait is a prime example of the credit risks of procrastination and complacency. Like a sandcastle, such a strategy may resist the waves lapping at its fortifications at first. But once it begins to crumble, the foundations can go fast. Fitch justifies Kuwait’s negative outlook revision with “near-term liquidity risk (…) in the absence of parliamentary authorisation for the government to borrow. This risk is rooted in political and institutional gridlock that also explains the lack of meaningful reforms (…).” The outlook change for Kuwait echoes the debt-ceiling crisis that led to S&P’s US rating downgrade (to ‘AA+’) in August 2011. Explaining the downgrade at the time, S&P said, “The political brinkmanship of recent months highlights what we see as America’s governance and policymaking becoming less stable, less effective, and less predictable than what we previously believed. The statutory debt ceiling and the threat of default have become political bargaining chips in the debate over fiscal policy.”

Speaking of the United States, Fitch’s outlook on the country has been negative since 31 July 2020, which the agency said reflects “the ongoing deterioration in the US public finances and the absence of a credible fiscal consolidation plan.” The latter is still elusive, but a stronger-than-expected recovery may yet stabilise America’s fiscal metrics enough for it to reclaim its ‘AAA’ rating from Fitch this summer. Meanwhile, S&P affirmed its ‘AA+’ rating for the US with a stable outlook on 16 March. In April 2020, S&P announced that it could downgrade the US in the event of “larger and more prolonged deterioration in public finances beyond our current expectations, without positive signals of future corrective actions.” Although the agency has made similar fiscally-oriented statements in previous years, S&P’s downgrade scenario for the US is now significantly different. Today, S&P states that a negative rating action could be triggered by “unexpectedly negative political developments in the next two years that reduce the resilience of American institutions, the economy, and the effectiveness of long-term policymaking or jeopardize the dollar’s status as the world’s leading reserve currency.” No more reference to public finances, which were unceremoniously ditched as a risk factor. At the same time, S&P’s institutional and governance assessment — the lowering of which led to a downgrade a decade ago — is now top-notch once again. As Washington remains in the unrelenting grip of unmitigated partisanship, and just weeks after a sitting president’s false claims of a stolen election culminated in a mob storming the legislature, such a positive political reassessment is a bold call. But by S&P’s methodology, it was also a necessary call to prevent another downgrade given the rapidly deteriorating fiscal picture. Short of a calamity akin to a military coup, then, S&P’s US rating seems secure. The only other significant risk to the US’s rating seems to be rising government debt: S&P currently records US debt at 115% of GDP for 2021, while the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) estimate is a much higher 133%. In the past, such levels of debt have triggered S&P to lower ratings by one notch (such as Italy’s) — a downward adjustment S&P’s own methodology (§126) seems to call for. Stay tuned, but do not hold your breath.

Vietnam got an outlook revision from Moody’s, moving from negative straight to positive on 18 March. Such a step is unusual. The last comparable event was S&P’s January 2016 downgrade of Poland from a positive outlook, after the newly elected government began actually delivering on its campaign promises. Moody’s said that Vietnam’s new positive outlook is due to fiscal and potential economic improvements; reasons that, it is fair to say, probably did not appear overnight. Nor did the reason for Moody’s late 2019 negative outlook — i.e., administrative shortcomings in the management of state-guaranteed debt — disappear so quickly. As recently as 18 December 2020, Moody’s tersely declared that it had completed a “periodic review” that “did not involve a rating committee”. Accordingly, the agency took no action on that occasion. Three months later, a committee was finally called and changed Moody’s outlook on Vietnam from negative to positive. Rating users may well ask what the value of such a “periodic review” could be if it did not pick up on any significant changes that, shortly thereafter, led to such an unusual “double notch” outlook action. Agencies would better serve investors and avoid such unnecessary U-turns by publishing proper ratings updates following credit committees more frequently.

The award for the quarter’s unluckiest action undoubtedly goes to Fitch. In mid-February it revised the outlook on its ‘BB-’ rating of Turkey from negative to stable. Fitch based this action on what it called “Turkey’s return to a more consistent and orthodox policy mix under a new economic team.” It also gave special praise to the new leadership at Turkey’s central bank: “Monetary policy has been significantly tightened, international reserves have stabilized, and the Turkish lira has appreciated by 18% against the US dollar since early November.” Alas, in mid-March, President Erdogan fired Governor Naci Agbal after just four months in the job. Currency, bonds, and equity markets tanked in anticipation of a return to the bad old ways. To be sure, Fitch was not alone in having been taken in by Erdogan’s capricious move — such nasty surprises are an occupational hazard for ratings analysts. Sometimes, you are just unlucky.