Russia: the price of isolation – an approximation

Bernhard Obenhuber

Mar 08, 2022

It’s tragic to see Russia’s unwarranted invasion of Ukraine. It painful to see how innocent people displaced from their homes, or perish, or be separated from their families to defend their country against Putin’s aggressive regime. Many of us believe that ordinary Russian citizens do not support this war but are fearful of the very real repression of speaking up against it. This is the textbook definition of an authoritarian regime.

1998 – 2022

In 1998, the Russian financial crisis took place. The economy collapsed, poverty soared, and the government eventually defaulted on domestic debt and declared a moratorium on foreign debt. A similar development is unfolding today in 2022. Back then, the default and demise were inevitable because of economic mismanagement for decades. Today, it was the decision of one or a small group of men in power.

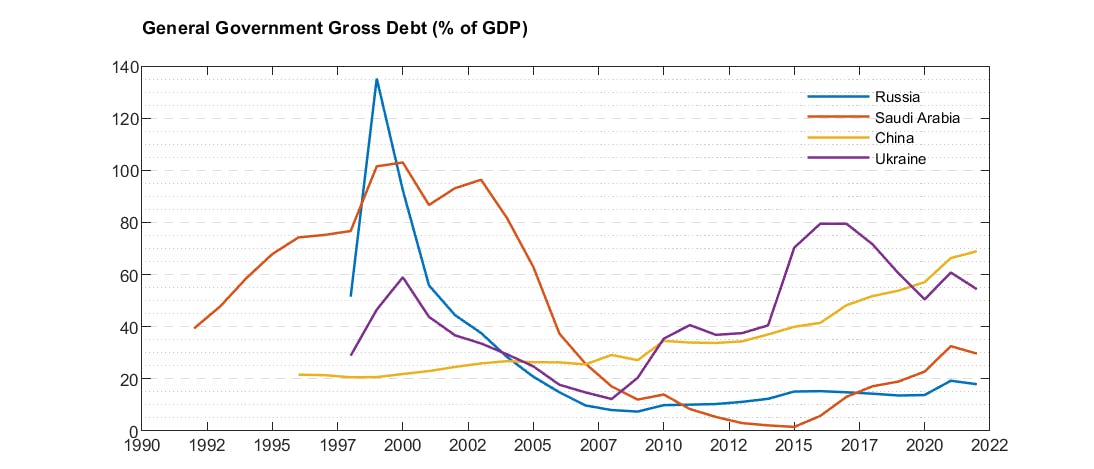

In the late 1990s, Russia had a severe debt problem. By contrast and on the run up to this war, Russia had very low levels of government debt and an arsenal of foreign currency reserves – both of which supported its investment grade rating of BBB- from the major credit rating agencies until last week. Russia could have run sizeable fiscal deficits for many years to get close to debt ratios of many other investment grade rated sovereigns.

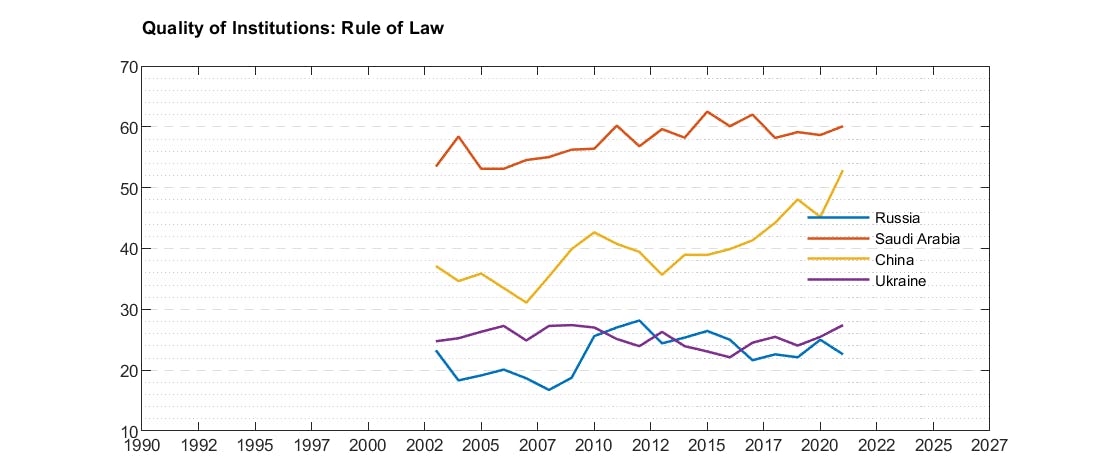

While the deleveraging of the sovereign balance sheet is clearly a very positive achievement and has been the credit rating strengths, several weaknesses remain such as the commodity dependency and lack of economic diversification. But the prime shortcoming has been the lack of progress when it comes to governance and quality of institutions. As the chart below and recent events show, Russia’s respect for the rule of law is weak – very weak.

Ability, willingness and (permission) to pay

Sovereign credit risk assessment focuses on the assessment of a country’s ability to repay debt (foreign) obligations (i.e. FX reserves, government revenues through tax income) and a government’s willingness to honor its obligations.

In 1998, the financial means were utterly deficient. Today, government solvency is/was very strong with very low levels of debt, high foreign currency reserves and a net foreign asset position. But countries rarely default because of solvency. More often, the lack of liquidity is the ultimate trigger. Given the unprecedented international sanctions, it is very likely that Russia will default on domestic and foreign currency government bond obligations that make it difficult to repay (because of the freeze of liquid assets and exclusion from payment systems). Refinancing or the issuance of new debt in international markets is not possible. Russia would need to turn to friendly regimes to do so. But the list of best friends is shrinking as well. Would China come to rescue as many anticipate or would it back off and wash its hands of supporting Putin’s war?

Scenarios:

Coming up with good scenarios for the way forward is difficult. Here are the three obvious ones:

- Super Bad: Russia wins the war and installs a government favourable to Moscow. This basically also means no more free elections in Ukraine and turns the country into a second Belarus. In such a scenario, harsh international sanctions will continue and the economy will deteriorate significantly. Russian, Ukrainian and Belarussian assets will remain uninvestable and the countries will be isolated. Further, the geopolitical situation will hang like a dark shadow over Europe.

Likelihood: High

- Bad: Russia retreats from Ukraine; Ukraine promises to be neutral and withdraws any NATO / EU aspirations. Russia claims victory in its echo propaganda chamber. Some sanctions are lifted (e.g. exclusion from Swift system) but investability would remain weak for as long as Putin is in power. The economy will muddle along but overall living standards will stagnate or decline.

Likelihood: Medium

- Good: Protests in Russia increase and lead to a change in government. Troops retreat from Russia. For such a scenario to materialize, it would be important that the military campaign runs into problems and is increasingly viewed as a failure by the Russian population. Given the military supremacy and iron fist over media in Russia, the likelihood of such a scenario is low.

Likelihood: Low

Sovereign rating implications:

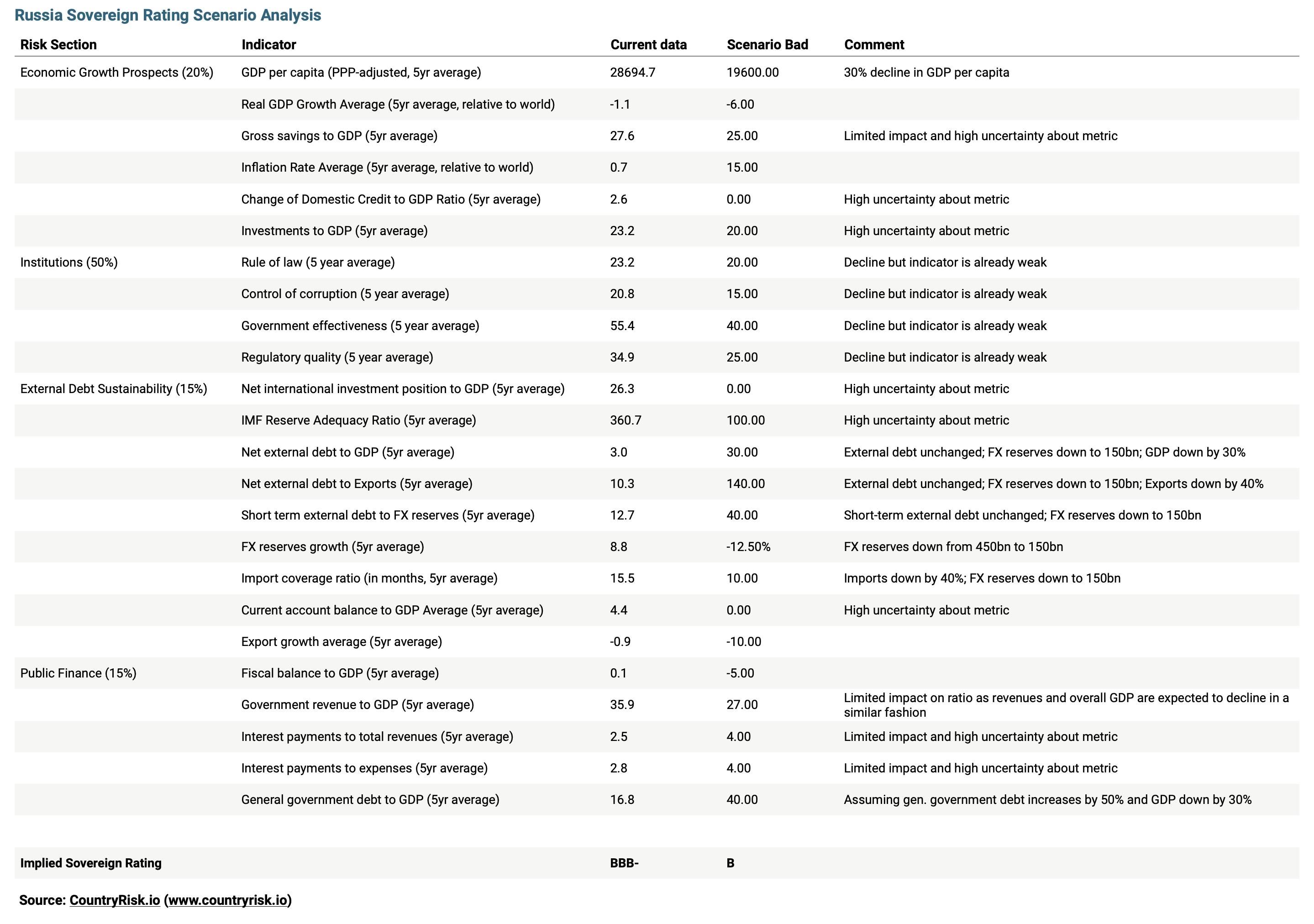

Based on the outlined scenarios, we ran some stress tests on the implied sovereign ratings based on our Sovereign Risk Score model that we calibrated for this purpose to the average of the three big rating agencies (Fitch, Moodys, S&P). Based on the current (pre-war) economic figures, Russia’s foreign currency sovereign rating would be BBB-. The indicators considered for deriving the rating are shown in the table below. The “Super Bad” scenario means sovereign default and the agencies would very likely withdraw the rating and coverage of the country. The second scenario “Bad” might lead to economic numbers similar to the Russian financial crisis in 1998 and as a result a rating of B. The “Good” scenario would be the investment grade scenario.

Rating agency reaction: From Hero to Zero

The big three rating agencies all rated Russia as investment grade at the beginning of this crisis. The strong government balance sheet and external position supported the rating while weak institutions and rather lackluster growth potential because of the strong commodity dependency were the key rating drags. Today, the sovereign rating of Russia is very different.

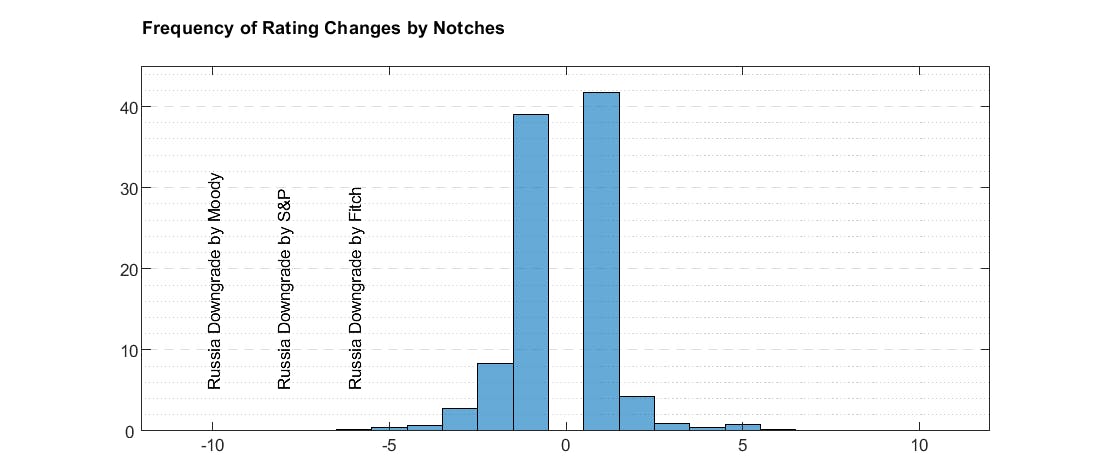

- Fitch: BBB => B (watch negative): 6-notch downgrade (Link)

- Moody’s: Baa3 => B3 (under review) => Ca (negative): 10-notch downgrade (Link)

- S&P: BBB- => BB+ => CCC- (negative outlook): initially one-notch downgrade in February followed by an eight-notch downgrade in March

Based on our knowledge and data, this is the first time that S&P downgraded by 8 notches in one action or 9 notches within a month. Moody’s 10 notch change is also exceptional. Only Fitch, moved by 10 notches on South Korea during the Asian financial crisis. Such rating change is very exceptional as the chart below shows. As all agencies either have a negative outlook, watch negative or under review, we are likely to see more downgrades or basically the declaration of default following a missed coupon payment – the next payment is due in mid March - and 30-day grace period.

ESG: Only one option

If an investor has only a hint of ESG in its investment policy statement, there is only one option: Divest all government and government-related assets as long as the current regime is in place. The fact that Russia brought war against Ukraine and its innocent citizens make such assets un-investable. The same applies to Belarussian assets. Full stop.

Several large asset owners and asset managers have already announced that they will divest Russian assets or at least mark down the assets to zero. It will be interesting to see how JP Morgan and other major investment indices providers – especially on the fixed income side – will go about Russian assets. JP Morgan announced on 7th March that all Russian assets will be excluded from their indices by the month end (Link).

Your own due diligence

While the purely quantitative scenario analysis shown above is instructive, we invite you to use the CountryRisk.io Rating Model to conduct a holistic sovereign risk assessment on Russia. You can upload your own dataset with your own forecasts and the platform will guide you through the analysis process. Book a call with our experts here: http://calendly.com/countryrisk/countryrisk-io-expert-call