Offshore Financial Centers in AML/CFT Risk Assessments

Bernhard Obenhuber

May 21, 2025

Offshore Financial Centers (OFCs) frequently come up in conversations with our clients when assessing AML country risk. In this blog, we want to share data-driven insights and reflections on how to identify OFCs and evaluate their role in money laundering and terrorist financing (ML/TF) risks.

What constitutes an Offshore Financial Center?

Most practitioners seem to recognize an OFC when they see one, yet defining it in a precise and practical way remains challenging. The most commonly referenced document is the IMF’s 2000 Background Paper on Offshore Financial Centers (Link), along with the U.S. Department of State’s 2004 report (Link). While both are over two decades old, their definitions continue to hold significance.

The IMF report highlights the ambiguity of the term:

“At its broadest, an OFC can be defined as any financial center where offshore activity takes place. This would include all major financial centers in the world.”

It further refines the scope by noting that OFCs typically exhibit several characteristics:

- A significant number of financial institutions primarily serving non-residents;

- Financial systems with external assets and liabilities that are disproportionate to domestic economic activity; and

- Features such as minimal or no taxation, lenient regulatory frameworks, banking secrecy, and anonymity.

For this blog, we focus on two core elements of the definition:

1. Identifying countries with disproportionately large financial sectors;

2. Assessing whether these countries are flagged by international organizations for deficiencies related to ML/TF, especially concerning anonymity and transparency in beneficial ownership.

To identify jurisdictions with exceptionally large financial sectors, we follow the methodology presented in the BIS Working Paper “Cross-Border Financial Centres” by Pogliani and Wooldridge from 2022 (Link). The authors note the challenges of relying on regulatory or tax attributes, which tend to be qualitative and challenging to quantify.

Instead, they propose a quantitative approach:

Cross-border financial intermediation, defined as the minimum of a country’s external financial assets or liabilities. This focuses on the jurisdiction’s role as a conduit for global capital flows, rather than a source or destination of funds.

We use BIS Locational Banking Statistics, normalized by nominal GDP from the World Bank. For smaller jurisdictions not included in World Bank data—such as Gibraltar, Jersey, and the British Virgin Islands, among others—we have supplemented our data with other credible sources. Although the quality of data varies, particularly for smaller Offshore Financial Centers (OFCs), this approach allows a structured comparison.

The chart above illustrates a strong correlation between GDP and cross-border financial intermediation. To identify “outsized” cases, we estimate a model where GDP explains financial intermediation and then calculate residuals. Countries with the largest positive deviations are those where the financial sector is disproportionately large relative to their economic size. Therefore, let’s revisit the chart and add the country codes of the top 30 outliers.

Notable outliers include:

- Cayman Islands

- Jersey

- Guernsey

- British Virgin Islands

- Luxembourg

- Switzerland

- United Kingdom

This metric offers an effective means to rank countries based on the relative scale of their financial sectors.

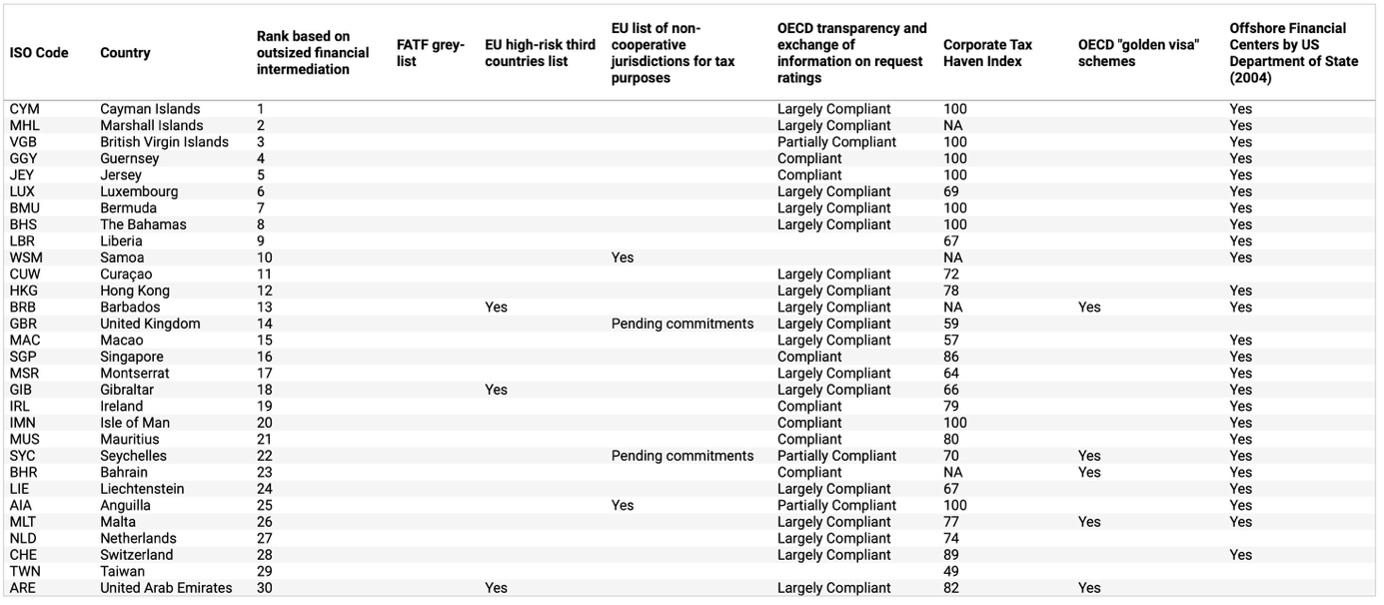

Step 2: Overlaying ML/TF Risk Assessments

A large financial sector alone is not necessarily a red flag; it may indicate political stability, strong institutions, or financial expertise. Therefore, we overlay the top 30 outliers identified in Step 1 with independent assessments of ML/TF risk.

We consider the following frameworks:

- FATF Grey List: Jurisdictions under increased monitoring that are actively working with the FATF to address strategic deficiencies in their frameworks for combating money laundering, terrorist financing, and proliferation financing.

- EU List of High-Risk Third Countries: Jurisdictions identified by the European Commission as having strategic deficiencies in their anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing (AML/CFT) regimes.

- EU List of Non-Cooperative Jurisdictions for Tax Purposes: Comprises countries that have either failed to meet their commitments to implement tax good governance standards within an agreed timeframe or have declined to do so.

- OECD Ratings on Transparency and Exchange of Information on Request: The Global Forum conducts peer reviews to evaluate jurisdictions’ compliance with the standard for exchange of information on request (EOIR) and assigns ratings accordingly.

- OECD Assessment of “Golden Visa” Schemes: While residence and citizenship by investment (CBI/RBI) programs may serve legitimate purposes, they also present potential risks for abuse—such as concealing assets offshore and circumventing reporting obligations under the OECD/G20 Common Reporting Standard (CRS).

- Corporate Tax Haven Index: Evaluates the extent to which a jurisdiction’s legal and regulatory framework enables or facilitates corporate tax avoidance, whether by design or effect.

- U.S. Department of State OFC Classification (2004): Identifies jurisdictions categorized as offshore financial centers based on the Department’s 2004 assessment.

Key Findings

- None of the top 30 countries with outsized financial intermediation are currently listed on the FATF grey list. The FATF assessments examine, among other factors, whether authorities are able to identify and trace beneficial ownership (Immediate Outcome 5), as well as compliance with Recommendations 24 and 25 on the transparency of legal persons and arrangements.

- Gibraltar and the United Arab Emirates were recently removed from the FATF grey list, yet they remain on the EU list of high-risk third countries, along with Barbados.

- The OECD’s ratings on transparency and exchange of information, the British Virgin Islands, Seychelles, and Anguilla are rated “Partially Compliant”—the second-lowest rating assigned. All other countries in the group have either a “Compliant” or “Largely Compliant” rating.

- Several jurisdictions—particularly within the top 10—are classified as corporate tax havens. While such classifications raise concerns around tax evasion and its broader societal impact, we do not automatically equate low corporate tax rates with an elevated money laundering risk.

- Some notable jurisdictions—such as Cyprus, Monaco, and Panama—do not appear among the top 30. This suggests that, based on our methodology, their financial intermediation is not disproportionately large relative to the size of their economies.

Conclusion

Identifying OFCs and evaluating their role in money laundering risks requires quantitative and qualitative analysis. By combining data on cross-border financial intermediation with independent ML/TF risk assessments, we get a clearer picture of which jurisdictions may merit closer scrutiny.

A large financial sector does not equate to financial crime—but where anonymity, secrecy, and weak oversight converge, the risk rises. Regular, data-driven reviews are essential for informed risk assessments in today’s globalized financial system.