Lebanon’s long recovery will need to build in ESG concerns

Bernhard Obenhuber

Aug 20, 2020

This blog post first appeared inInvestment Week.

The deadly blast at the port in Beirut came at a time when the prospects for Lebanon’s economy and its sovereign bonds were already extremely bleak, following years of mismanagement and neglect of environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks. Financial pledges from a number of nations will bring economic aid to the country. But these will be a sticking plaster solution unless the nation can right its path and put ESG factors front and centre in its recovery plan.

Lebanon’s unique social structure

Lebanon’s economy has long been weighed down by a number of complex social factors. A small nation of 6.8 million, Lebanon is temporary home to more than 1.5 million refugees, the vast majority of whom are from neighbouring Syria. No country in the world hosts more refugees per capita. As can be expected, this has created severe economic, security and social impacts on the nation. The governor of Lebanon’s central bank said that, based on a study by the World Bank, Syrian refugees impose a direct cost of about $1 billion a year and an indirect cost of $3.5 billion on Lebanon.

While foreign donors have stepped up to support Lebanon, aid has been curtailed by the fact that Hezbollah had ministers in the cabinet. The Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States, among others, consider Hezbollah to be a terrorist organisation. And, earlier this year, the Iranian-funded group accused the US of trying to influence the appointment of top Lebanese banking officials, further complicating an already fragile relationship.

Lebanon’s dependence on remittances has also put it in a vulnerable position. Last year, remittance payments were estimated at $7.3bn (12.5% of Lebanon’s GDP). The country’s large and widespread diaspora typically sends more money home during times of crisis, but the impact of Covid-19 has cut the inflows upon which the nation has often relied to finance its large external deficits. Ali Awdeh, head of research at the Union of Arab Bankers in Beirut, predicts Lebanon will be among the top 10 countriesmost hit by the decline in remittances, based on their percentage contribution to GDP.

Corruption, cronyism, and a catastrophe

As Lebanon endures economic crisis, much of the blame falls at the feet of its politicians. Simmering tensions led to the October Revolution last autumn where citizens rallied against sectarian rule, a stagnant economy, high unemployment, endemic corruption in the public sector, and legislation, such as that relating to banking secrecy, that is perceived to shield the ruling class from accountability.

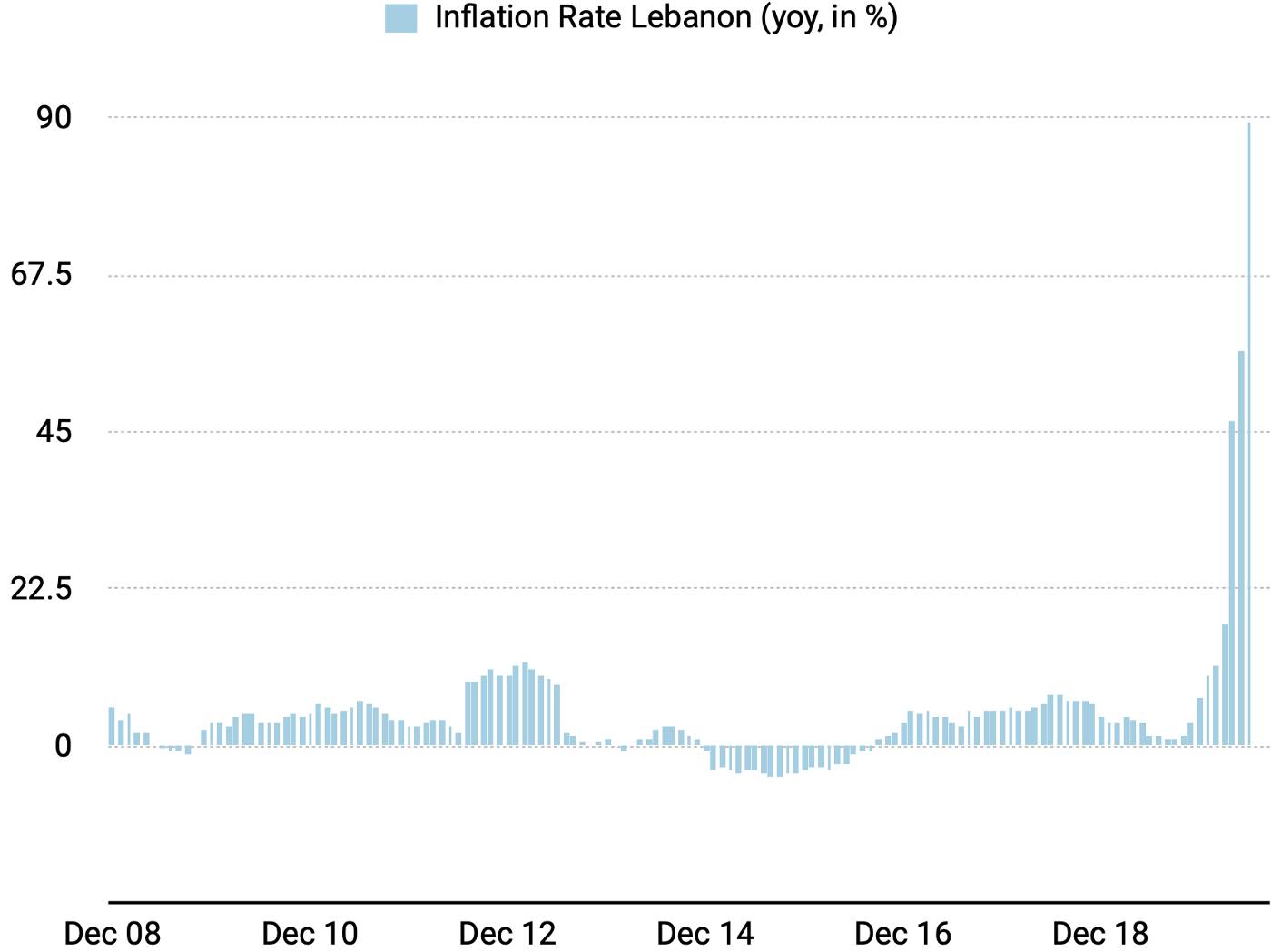

Three hundred days have passed since the protests erupted, and the myriad of problems facing the nation continue to grow. The Lebanese pound has lost about 80% of its value on the black market against the dollar since October. As a nation dependent on imports, inflation has correspondingly skyrocketed. The government defaulted on its debt payments and halted a bond payment of $1.2 billion in March, and a two-month lockdown to contain coronavirus further handcuffed the economy. Informal capital controls have also prevented transfers and restricted withdrawals in dollars, weakening trust in the banks and leaving citizens unable to access their savings.

The banking system has been described by many critics as a Ponzi scheme. Lebanese banks have been paying out sky-high interest rates to large depositors from the interest earned on the money they have lent to the government. It comes as no surprise that this setup, where private enrichment is funded by increased public debt, has become unsustainable. By using capital to provide a stable dollar peg for the Lebanese pound rather than investing in improving economic productivity, economic collapse was on the cards.

This is just one of many failures by the Lebanese government, which went without a budget for 11 years until finally approving one in 2017. The country’s political order is based on the idea that power sharing and sectarian quotas for the country’s various religious and confessional groups is the only way to preserve civil peace, and that this formula should extend to the way public funds are allocated. Consequently, politicians, chieftains and their cronies benefit financially. Lebanon’s top 1% earn about 25% of the nation’s GDP, making it one of the most unequal states in the world.

Last week’s tragic port explosion was the latest case of mismanagement by the Lebanese government. Despite customs officials proposing exporting the 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate, giving it to the army, or selling it to an explosives company, no action was taken because the judiciary’s approval could not be obtained. On Monday, the Lebanese government resigned in the wake of the deadly blast that killed over 200 people.

Political reform in Lebanon has finally reached a tipping point. The IMF has warned Beirut it will not get any loans unless reforms are carried out and the financial system is solvent. Nations such as Canada and France have already taken action to ensure their aid bypasses the government level to avoid any corrupt use of funds.

Lebanon’s recovery requires a two-pronged approach involving both humanitarian and political aspects. First and foremost, action must be taken to address food shortages, overrun hospitals, and provide shelter for displaced persons in the wake of the Beirut explosion. Once support for the humanitarian crisis has been provided, economic, social and governance challenges must be tackled through political reforms, restructuring the economy, and greater support from the international community for the 1.5 million refugees the country hosts in order to get Lebanon back on a path to recovery.