Country risk: The hunt for premia

Bernhard Obenhuber

Apr 11, 2024

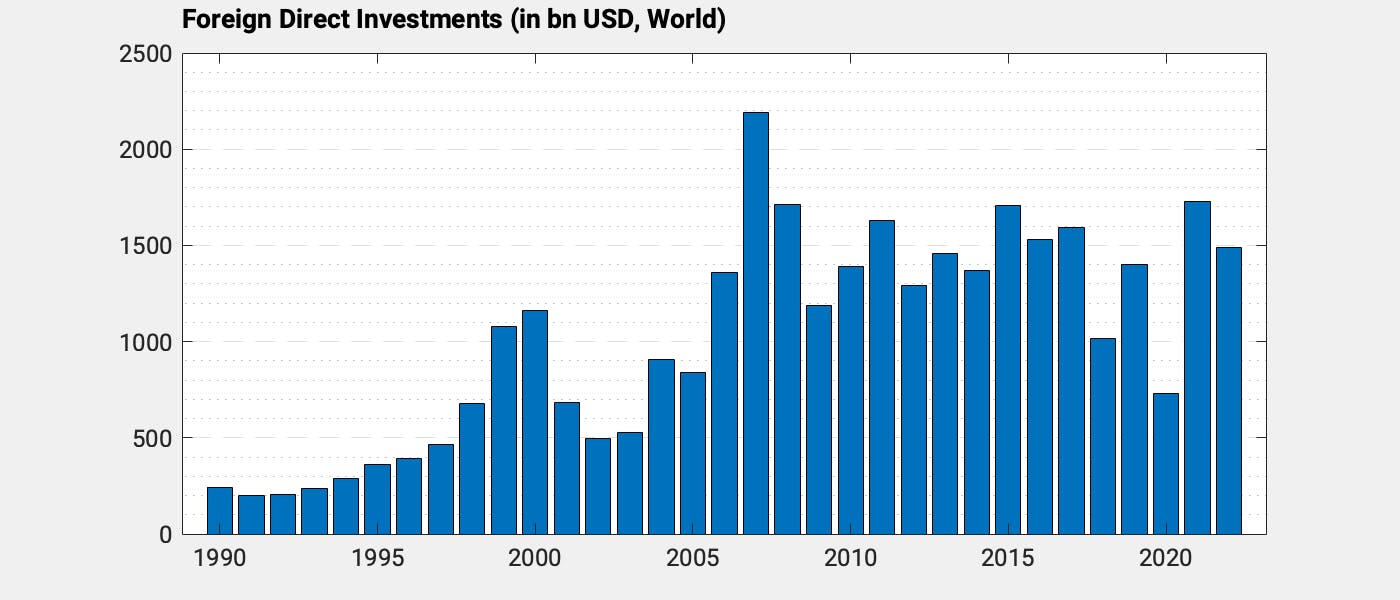

USD 1,489,756,000,000 – This amount was invested as foreign direct investments in 2022 based on UNCTAD data. Now to get to this number, this must have involved countless meetings and hours of deliberation to determine whether it is a good idea for a company to build or invest in production facilities in a foreign country. What could go wrong? How do companies select the right country?

This blog post zooms in on the issue of coming up with the appropriate country risk premium that enters the valuation calculation in deciding whether to invest abroad.

Spoiler alert: We have not found the magic ball and it is not 42.

Country risk: fuzzy, fuzzy, fuzzy

Anyone who has ever searched for country risk (premium) will have at one point come across the webpage of NYU corporate finance professor Damodaran. How does he define country risk as a step towards measuring it:

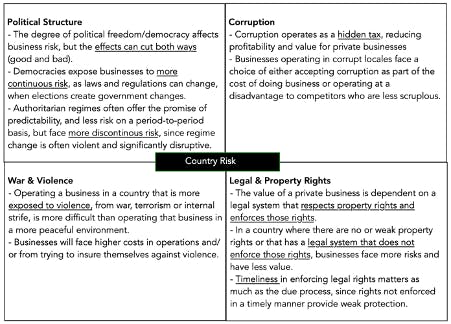

“What makes some countries riskier than others to operate a business in? The answer is complicated, because everything has an effect on risk, starting with the political governance system (democracy, dictatorship or something in between), the extent of corruption in the system, the legal system (and its protection for property rights) and the presence or absence of violence in the country (from wars within or without). The table below, which I have used in prior updates, captures the main drivers of country risk:”

In the most simplistic terms, one might say that country risk is everything that is outside of the control of a manager. For example, the government in a foreign country might retroactively change the rules of the game; or a war might break out; or capital controls might prevent the company from repatriating earnings.

Or one can also focus on transfer and convertibility risk – the risk that a company cannot exit a country (think foreign companies that have subsidiaries in Russia and found it difficult to close shop immediately when it decided to invade Ukraine) – is also core to the OECD definition of country risk but it then goes on to include “everything” else as well and it tries to distinguish country risk from sovereign risk.

“The country risk classifications are meant to reflect country risk. Under the Participants’ system, country risk encompasses transfer and convertibility risk (i.e., the risk a government imposes capital or exchange controls that prevent an entity from converting local currency into foreign currency and/or transferring funds to creditors located outside the country) and cases of force majeure (e.g. war, expropriation, revolution, civil disturbance, floods, earthquakes).

The country risk classifications are not sovereign risk classifications and therefore should not be compared with the sovereign risk classifications of private credit rating agencies (CRAs). Conceptually, they are more similar to the "country ceilings" that are produced by some of the major CRAs.”

Source: OECD (Link)

We need a number

However you want to define country risk, i.e., simple or with a twist of transfer and convertibility risk, it’s difficult to put a fuzzy country risk narrative into a valuation spreadsheet. So, we need to have a number to calculate the expected (present) value or internal rate of return of our foreign direct investment cash flows. This allows us to compare different investment opportunities and select the best ones. What options do we have?

We are aware of three publicly available sources. We discuss each below:

Let’s circle back to Damodaran

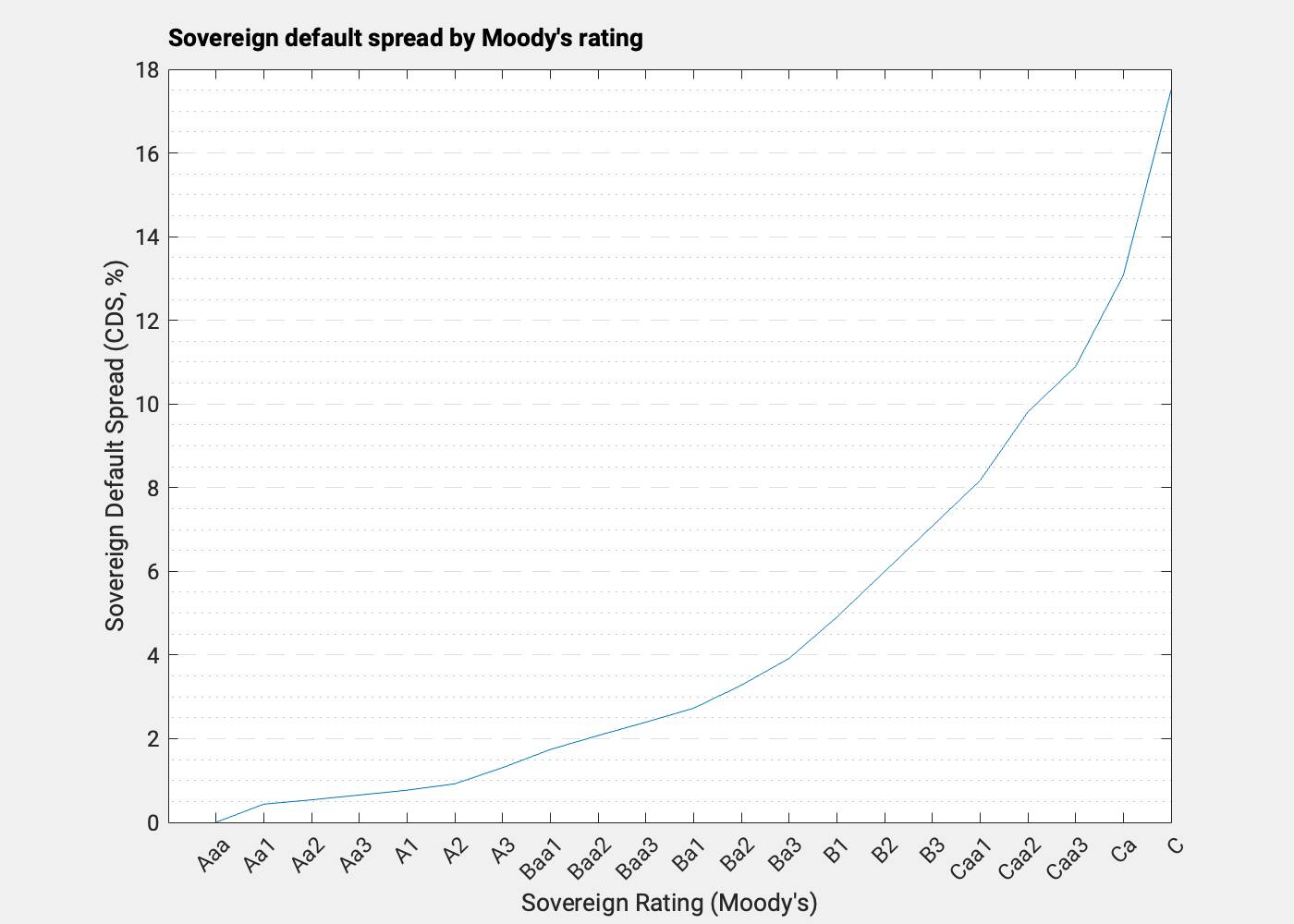

The first and by far the most often cited one comes from Prof. Damodaran. He publishes updated country risk premia for basically all countries on a regular basis. You can find the latest spreadsheet update for January 2024 here (Link). But how does Damodaran’s country risk premium crystal ball work? He focuses on the default spread for a country and provides two options. Either you take the historical default probability of government bonds using local currency sovereign ratings from Moody’s. (Remember the OECD statement from above: country risk ≠ sovereign risk). Or, you accept the other option and use the 10-year CDS spreads for the respective country rating. The second option gives risk premia from 0 for the highest rated countries and up to nearly 18% for the lowest rated ones.

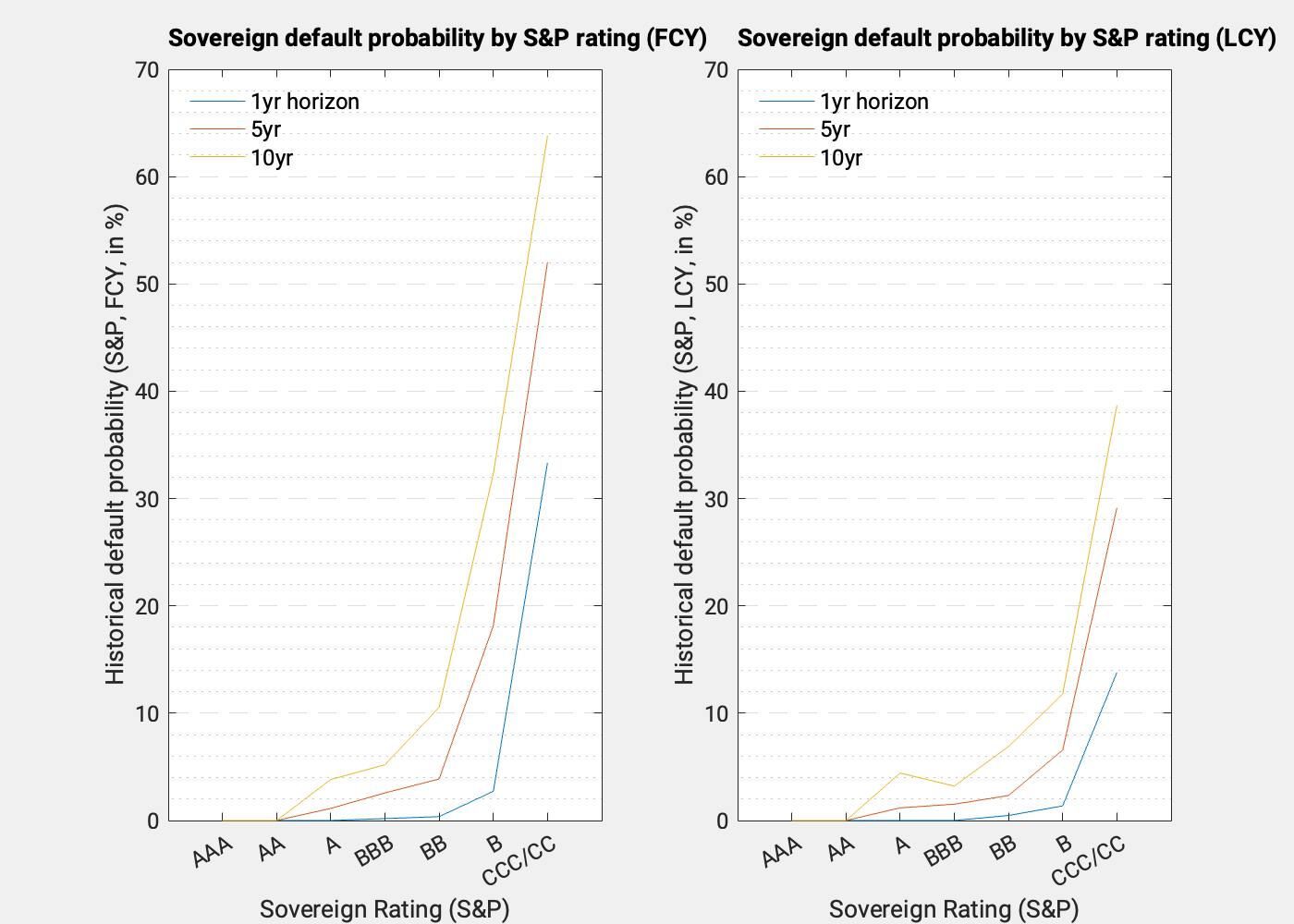

We all know that CDS data can be quite volatile and might also reflect other risk factors than purely the sovereign default risk. That’s why a look at actual historical default probabilities can be instructive. The charts below show the local and foreign currency sovereign default statistics by S&P for various rating buckets and time horizons (on a cumulative basis). For instance, there is a nearly 7% probability that a country rated BB initially will default on its local currency debt obligations by year 10; or 10.5% for foreign currency obligations. To convert to a premium, it’s instructive to adjust for the fact that not all capital is lost in the case of default because there is still some recovery value.

In addition, to use it as a premium for valuation purposes you need to convert it to an annual basis by taking the average per year or by calculating marginal probabilities between the years. And by doing so, we arrive at the lower premia than compared to taking CDS spreads.

CDS or sovereign bond spreads give the most granular risk premia. However, we would recommend using a CDS curve based on averages over the business cycles for the various ratings. This reduces the risk that a long-term project is evaluated with a country risk premium extracted from CDS during a crisis period where spreads might be distorted by other factors such as illiquidity and global risk appetite.

Or there’s the OECD country premia

Many of our readers might be familiar with the OECD country risk classifications for the risk definition mentioned at the beginning of the post. The assessments are typically updated four times a year and combine a quantitative and qualitative approach. The quant model was recently updated and the Swedish export credit agency EKN published an interesting blog post on it here (Link). The risk classifications range from Category 1 – 7. Risk category 1 has not been assigned to any country for some time and “High Income OECD countries and other High Income Euro zone countries” are not assessed. You can find the current and previous assessments here (Link). The risk classifications are crucial as they drive the cost for export finance, called Minimum Premium Rates in OECD terminology. Here is the definition:

Minimum Premium Rates: The Arrangement stipulates that no less than the applicable Minimum Premium Rate (MPR) shall be charged to account for the credit risk when providing an officially supported export credit. Premium is charged in addition to CIRRs, as it is meant to cover the risk of non-repayment of the export credits. The Premium rates depend on the level of risk, which includes the country risk (see the page on country risk classification), time at risk and the political and commercial risk covered.

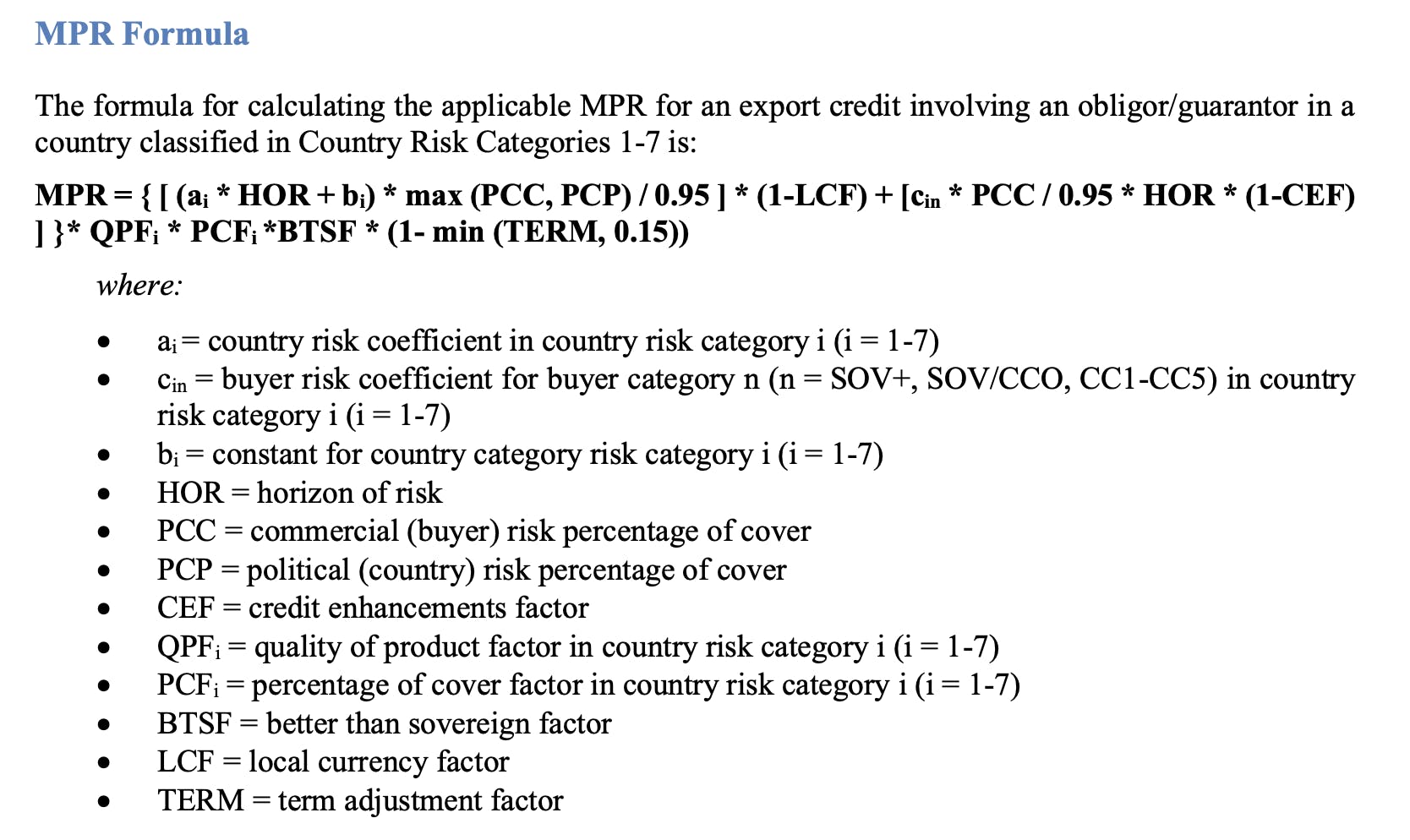

The prevailing applicable MPR for countries rated from category 1 to 7 (see country risk classification) are derived using a complex formula provided in Annex VIII of the Arrangement.

Source: OECD (Link)

So, let’s search for this complex formula. But first, we need to do some digging to find the respective report (Link) and the equation. Someone must have had fun coming up with it.

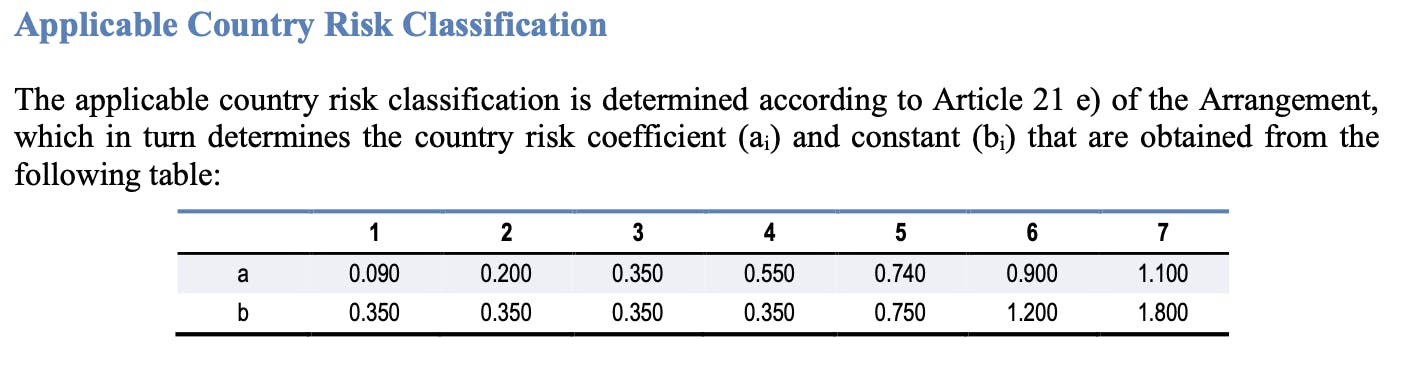

Out of the various components, we are only interested in the first part (a * HOR + b). The remaining components are more related to the credit risk of the borrower or trade partner. The document also gives the actual numbers for coefficient “a” and constant “b”.

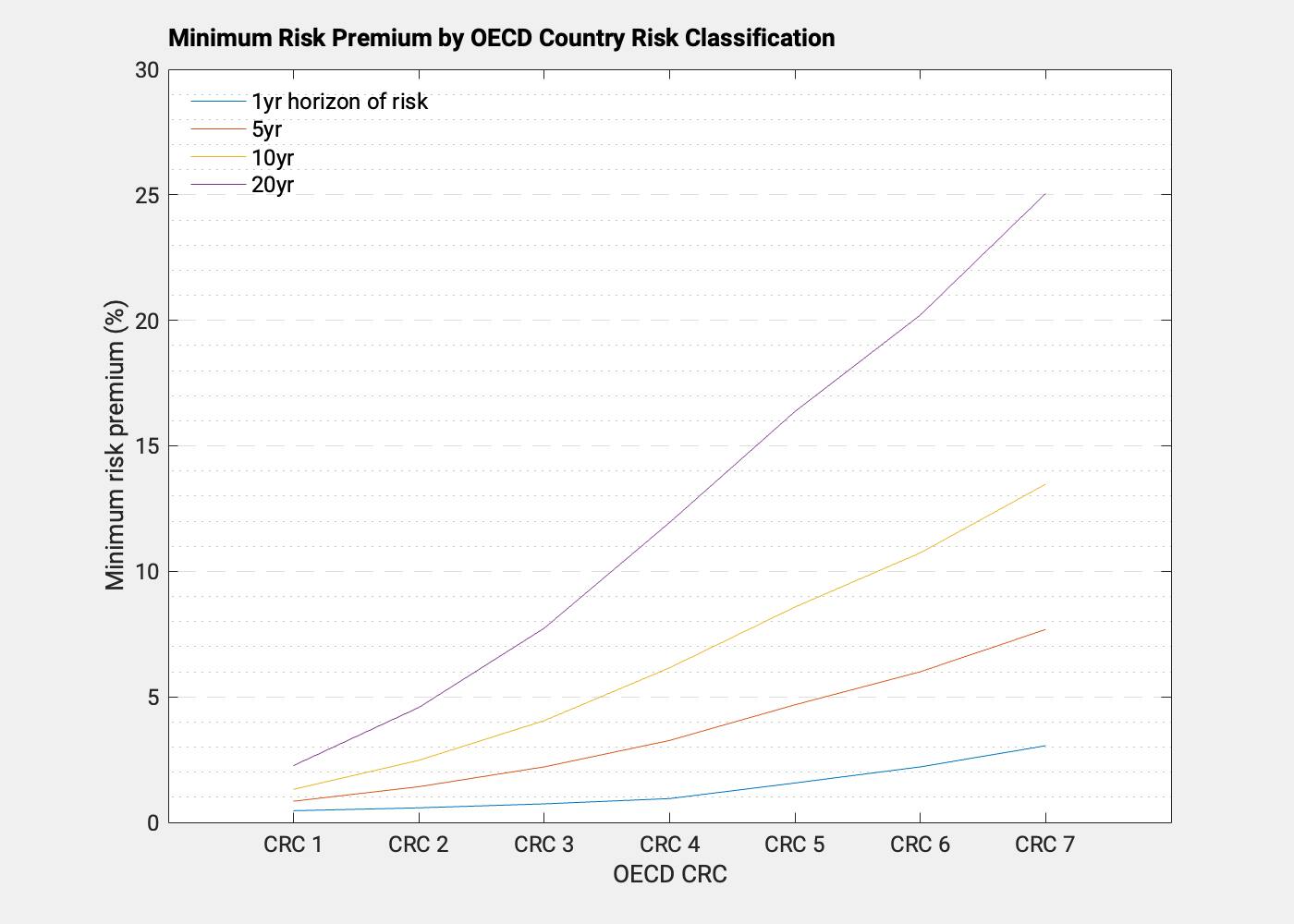

Armed with that information, we can calculate the country risk premia for various risk categories and time horizons that we plot below.

For instance, the risk premium that we need to add for countries with a CRC 5 risk classification (e.g., Albania, Algeria, Georgia, Paraguay, Uzbekistan) and a five-year horizon is around 4.7% (on top of the respective risk-free currency curves). Unfortunately, it is not public knowledge how the coefficient and constant are derived. If a reader have some insights, I would happily sponsor a bottle of wine.

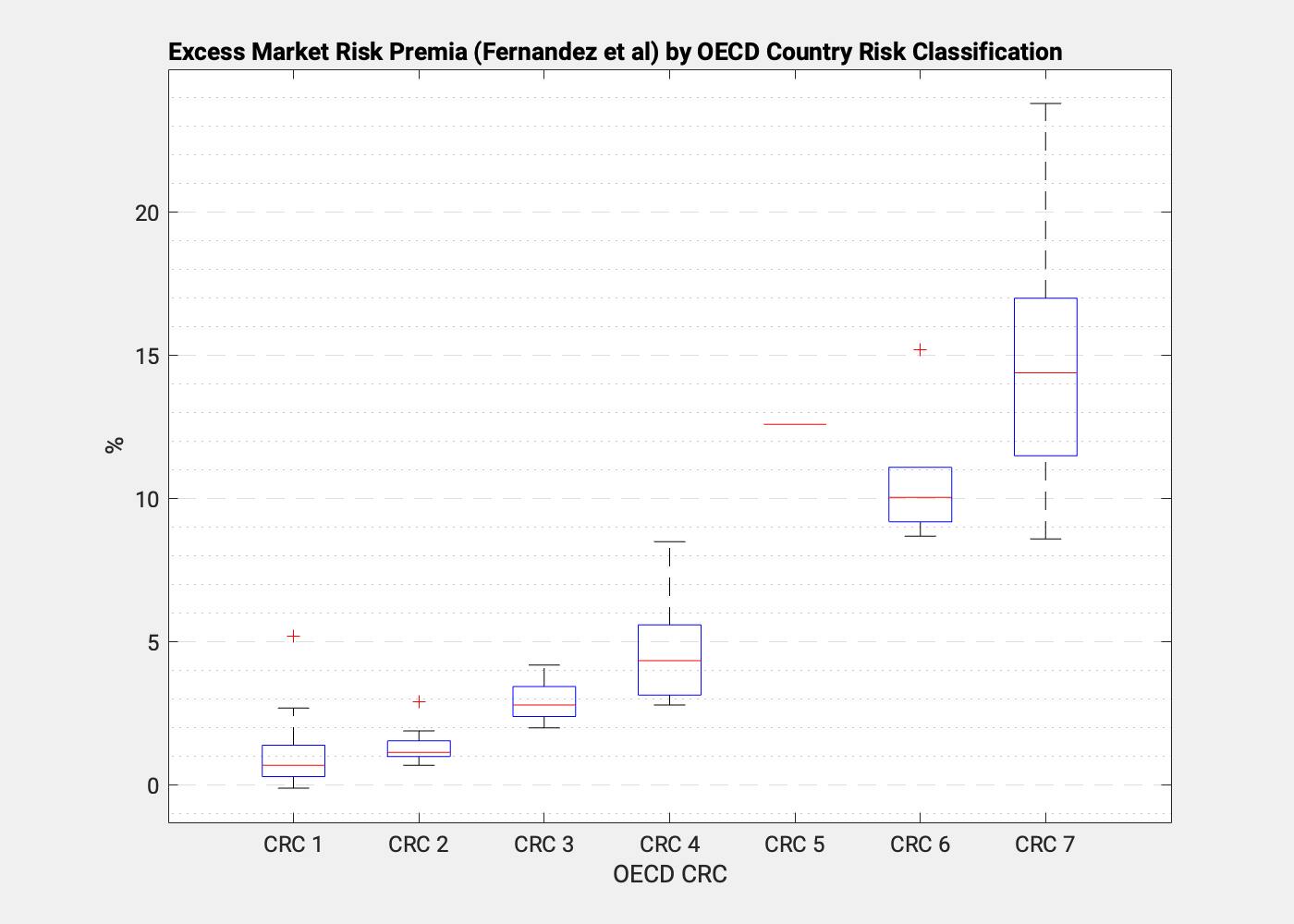

Then there’s the survey-based premia

The third source for country risk premia that we are aware of and that is publicly accessible comes from Pablo Fernandez et al. (Link), professor at Spanish business school IESE. He regularly sends out emails to around 15,000 people asking them for Market Risk Premium “to calculate the required return to equity in different countries”. Not directly a country risk premium, but we can use the delta between a basket of mature markets and other countries. When we relate this to the OECD country risk classifications, we get a picture that is not too different from the previous two approaches – with some stretch of imagination.

In conclusion, country risk might just be in the eye of the beholder

In our view, the most important factor is that country risk needs to be defined for your specific company or at least sector. The operational definition of country risk for a company in a highly regulated industry with long investment cycles (think about building infrastructure in a foreign country) should be a different one than for a company that invests in manufacturing capacity for producing clothes where reputational risks due to human rights violations have a higher priority.

Only if you have a clear definition of country risk for your organization can you search for useful metrics to track risks over time, identify trends and compare countries. This will also allow you to derive a risk narrative for each country that you and your stakeholders (e.g., C-level) can relate to. A generic country risk definition will provide only very limited insights. Yes, we know that Norway has a low country risk and Yemen has very high risk. To be useful, the country risk definition needs to differentiate within a peer group. And for that the country risk definition needs to be as specific as possible.

If you have your country risk definition and risk categories, you can attach specific figures for a country risk premium. We would utilize all three approaches mentioned above and either average the country risk premia across them or apply separately to derive a valuation range.

We hope that this blog post gave you some insights on available country risk premia and their challenges. We would love to hear how you tackle this thorny issue of coming up with numbers for your cost of capital and valuation calculations.

In an upcoming blog post, we will touch in more detail on the point of building a bespoke country risk score. Stay tuned.