Clean Money Matters: Why AML is vital for truly sustainable investing

Bernhard Obenhuber

Mar 31, 2023

The 1987 United Nations Brundtland Commission defined sustainability as, “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” This definition has stood the test of time. And, within the last decade, sustainability has become a dominant theme in the marketing messages, product development, and corporate strategies of many large investment firms.

At CountryRisk.io, we welcome this trend, as we believe that sustainability is vital to the long-term success of every nation. It is also central to our values, and the Brundtland Commission’s definition of sustainability—along with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—serve as our sustainability touchstones.

A country’s natural capital is an endowment that belongs to each of its citizens, and sustainable investing plays a crucial role in preserving it for current and future generations. But one component of this project is often overlooked: the imperative to clean up corrupt capital.

Capital for gains

Building a more sustainable future requires substantial capital. For instance, a research report[1] commissioned by the the UN High-Level Climate Action Champions, Vivid Economics estimated that achieving net zero will require around USD 125 trillion of climate investment by 2050.

The report also concluded that this financing cannot and should not come solely from the public purse, but also from private capital. We can all vote with our money by investing in themes and causes that are important to us. As little as ten years ago, the list of sustainable investment products was extremely limited; but today, we can choose from an abundance of sustainability-focused offerings. However, while investors are doing a fantastic job in the area, greenwashing is still a significant challenge that needs to be addressed by educating investors and enhancing regulations.

Asset managers and private banks have invested heavily in designing the investment processes, analytical competence, and marketing material around sustainable investing, and they take several different approaches to mitigating greenwashing. These include excluding certain countries, sectors, or companies; identifying the sustainability leaders within a given asset class; and impact or activist investing.

Here, we’ll examine the issue through the somewhat high-level lens of the following subtopics:

- Environment (e.g., climate change, biodiversity)

- Social (e.g., inclusion, equality, human rights)

- Governance (e.g., corruption, bribery, fraud)

Where’s the capital coming from?

Asset managers require diligent selection processes to ensure that the substantial capital being invested makes its way to those projects that are making genuine and important contributions to building a sustainable future. However, equal scrutiny must be paid to the sources of capital. If the funds are ultimately derived from, say, illegal logging activities, exploitation of child labour, or bribery, then no matter where the money goes, the investment won’t be truly sustainable. So, for asset managers who take sustainable investing seriously, the know-your-client process is far more than a tickbox compliance exercise.

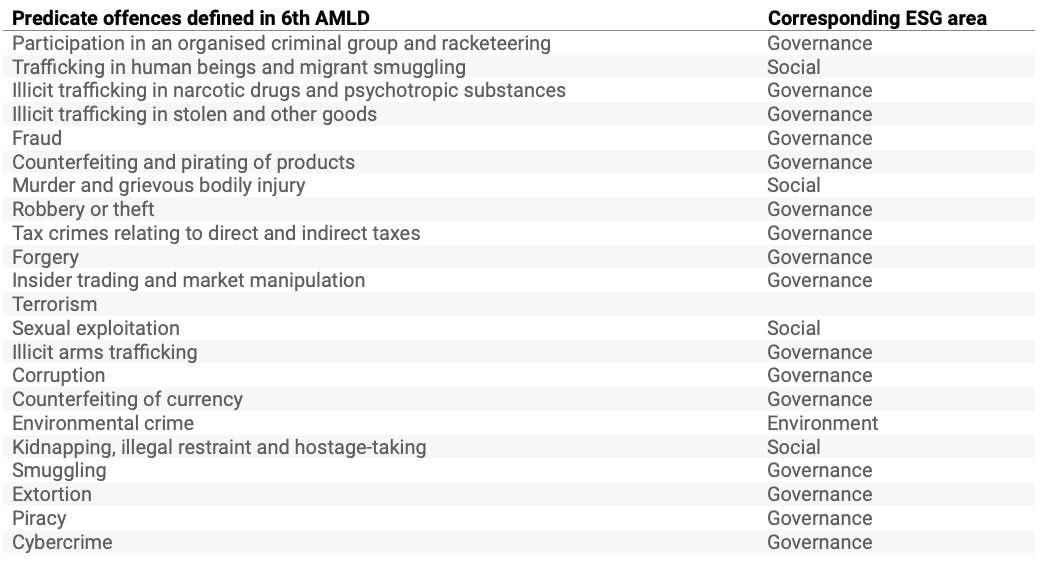

For the most part, we can map the kinds of predicate offences that generate such “dirty money” to the subtopics of ESG investing. In its latest 6th Directive on AML 22 (AMLD), the EU defined the following predicate offences, each of which we’ve mapped to an ESG subtopic:

Most of these predicate offences fall under the Governance subtopic. However, Environmental crimes (e.g., wildlife and pollution crimes, or illegal fishing, logging, and mining) and the human rights violations captured by the Social subtopic are also significant sources of dirty money. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF), which publishes various reports (Link) on environmental crime, estimates that such activities generate around USD 110 to 281 billion every year. That’s a lot of dirty money for criminals to launder, which they often attempt to do by investing it through reputable financial institutions.

The link between AML country risk and ESG country performance

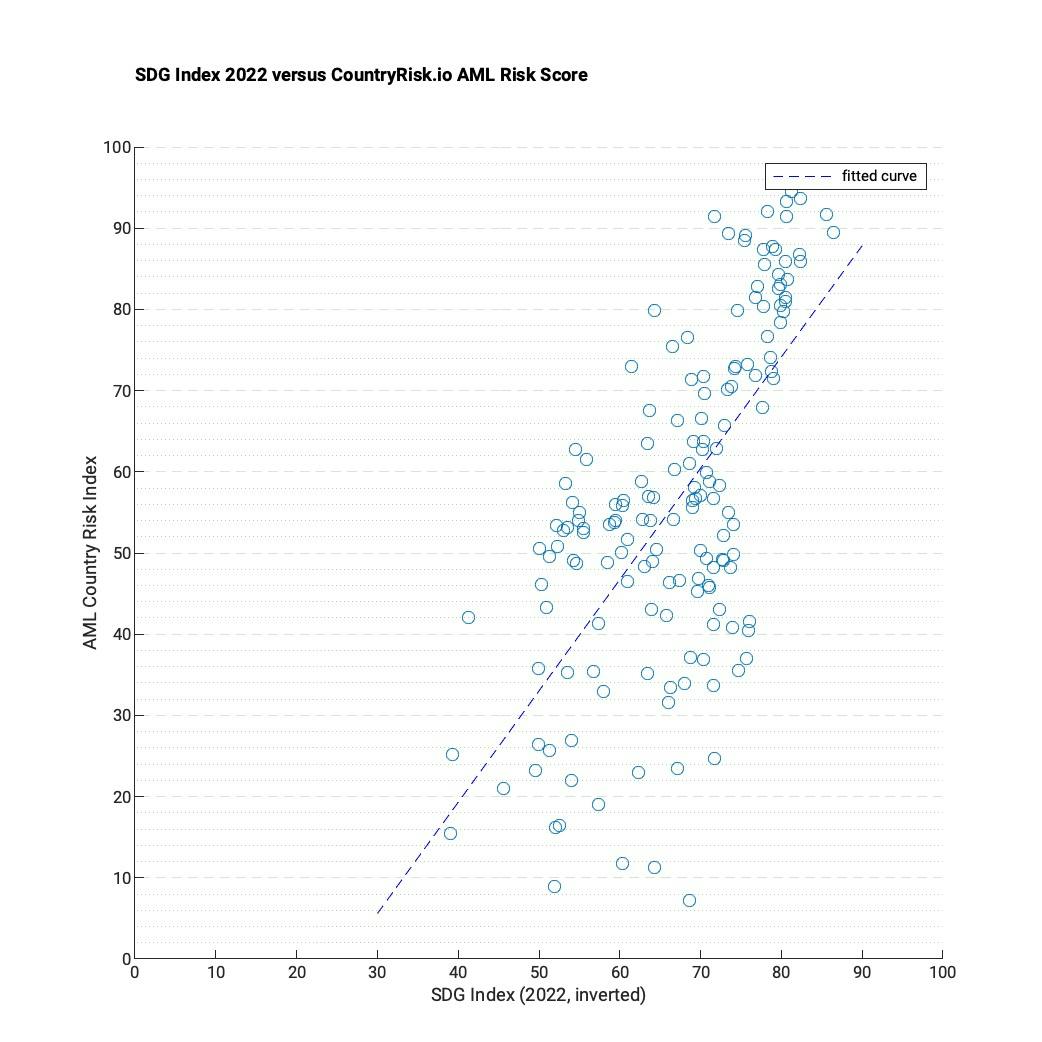

One way to understand the relationship between AML country risk and ESG country performance is to compare our CountryRisk.io AML risk score with the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network’s (SDSN) Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Index, which we believe is a good reflection of countries’ ESG performance. We’ve plotted these measures against each other in the chart below (we inverted the SDG Index for better readability), with higher values indicating greater AML country risk or poorer ESG performance. As you’ll see, the there’s a strong correlation between the two measures.

Taken in isolation, compliance officers and portfolio managers are likely to agree that it’d be good to avoid investing in high-risk countries, as per the AML Country Risk Index. Beyond that, however, it’s possible to disagree on what we should conclude here. On the one hand, we also might want avoid investing in countries with poor ESG performance as indicated by the SDG Index since, as the chart shows, these countries also tend to carry greater AML risk. On the other, you could argue that we should invest more in countries with worse ESG performance, on the basis that you’re likelier to get more impact bang for your investment buck.

A holistic approach to sustainability

As well as by working with the underlying data, investment and compliance teams can learn a great deal from each other—especially at the country level. For example, wherever there’s a portfolio manager trying to decide whether to invest in bonds issued by a government known to harbour corruption, there’s also likely to be a compliance officer who needs to assess the money laundering risk of funds coming from that country. Promoting constructive communication between compliance and investment teams, then, can deliver significant savings of time and money through resource and knowledge sharing.

Whether you’re a compliance officer or an asset manager, a holistic approach to sustainability and sustainable finance requires both a diligent investment process and a thorough AML compliance check to ensure that clean money finds its way to clean investments. If either of these is missing, you will have no idea whether the investment in question is truly sustainable—or if it’s holding us back from a more sustainable future.

[1] Source: Link